Two years ago, the Air Transport Action Group (ATAG), of which GE Aerospace is a member, set an ambitious goal of achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050. To gauge the progress the industry has made toward that target, GE Aerospace this summer commissioned a survey of 325 aviation decision makers in the U.S., the U.K., China, India, the UAE, and France.

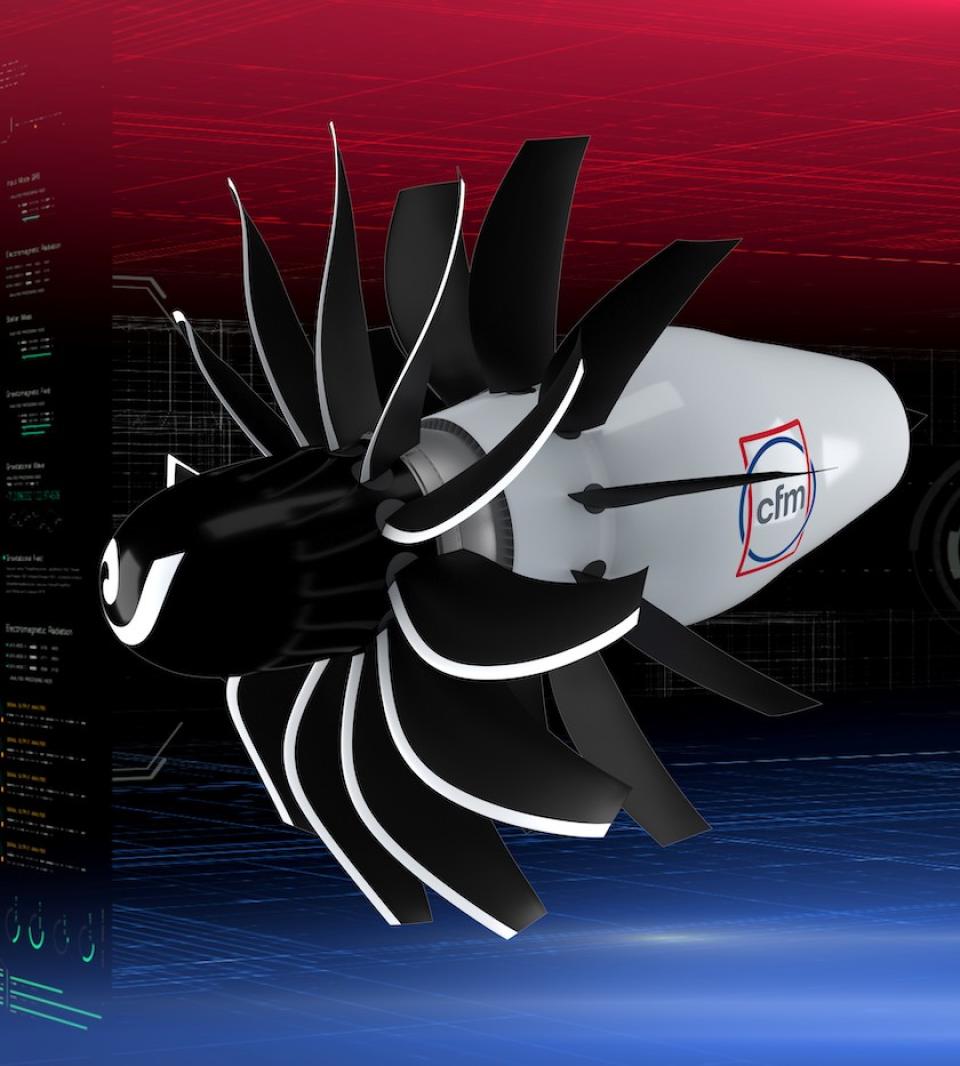

The scene about 36,000 feet in the air somewhere north of Seattle has shades of a techno-thriller: Two jets are loaded with an international team of experts from GE Aerospace, NASA, Boeing, German Aerospace Center (DLR), and elsewhere. A NASA DC-8, bristling with probes and sensors, pursues Boeing’s ecoDemonstrator Explorer, a 737-10 destined for United Airlines whose CFM LEAP-1B engines are operating with HEFA sustainable aviation fuel (SAF).

The dawn of the jet age gave birth to the concept of the global village. Once jet engines made the jump from military fighters to civilian planes in the 1950s, commercial passenger service could carry people farther and faster than ever before. Fares dropped, ticket sales quadrupled, and by 1972 almost half of all Americans had traveled by air.

Anyone who visited the GE Aerospace chalet last week at the Paris Air Show, on the grounds of Le Bourget Airport, came away with three distinct impressions: The market for engines is growing, lean is working, and new technologies are on the rise.

In 1941, the United States government asked GE to develop the first American jet engine. Allied defense, industrial collaboration, technological advancement, and economic growth were at stake. GE delivered the very next year.

Now, more than 80 years later, GE Aerospace finds itself at the cusp of another era-defining moment. With climate change impacting communities and economies around the world, the aerospace industry is in the midst of what feels to some like a seismic shift.

Next week at Le Bourget Airport, north of Paris, more than 300,000 people are expected to descend — many of them literally, from the skies — for the oldest and most important gathering of the aviation industry. It’s a tradition going back to 1909, when a Blériot type XI monoplane captivated showgoers after having completed, just months before, the first successful flight across the English Channel.

“There has never been a more exciting time in my 25-year career as an aerospace engineer,” said GE Aerospace General Manager of Advanced Technologies Arjan Hegeman yesterday in remarks before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation. The hearing, on “Advancing Next Generation Aviation Technologies,” was part of the Senate’s work on the 2023 FAA Reauthorization Act. “This era of innovation requires ongoing collaboration with federal agencies like NASA and the FAA,” Hegeman said.

With the summer holiday season underway, air travel has bounced back from its lockdown doldrums. But so has the awareness of commercial aviation’s impact on the climate.

Airlines and aircraft and engine manufacturers want to be part of the conversation.

Alex Hills developed a passion for 3D printing like most hobbyists: He bought a printer and began “tinkering around” with some simple print builds.

A decade ago, Hills, who works as a test hardware engineer at GE Aviation, printed his first generic jet engine design from plans he found online. “It was a real simple model that spun with some bearings,” he says. “I thought it was cool and printed another one that I put on my desk.”

It’s been four years since aviation fans, industry executives, aerospace engineers and investors last descended on the local airport in Farnborough, a quiet town about an hour southwest of London. Normally, the Farnborough International Airshow takes place every two years, alternating with the Paris Air Show. Together, they are the focal point for the aerospace industry. The pandemic disrupted this rhythm, but starting Monday the Farnborough show is back on track.