In 2020, after the COVID-19 pandemic had all but halted global air travel, about 50 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines employees began brainstorming big ideas to present to company leadership. One of these Bold Moves initiatives launched this spring. The Sustainable Flight Challenge will have KLM and 15 other carriers — all members of the SkyTeam Airline Alliance — operate 22 flights with the goal of beating their own personal bests in reducing carbon emissions. They plan to share all data they gather during the flights freely within the aviation industry to drive innovation.

Last November, a long-haul flight from London to Abu Dhabi operated by Etihad Airways notched an important aviation industry milestone by reducing the trip’s carbon emissions by 72% compared with an equivalent flight in 2019, using existing technologies.

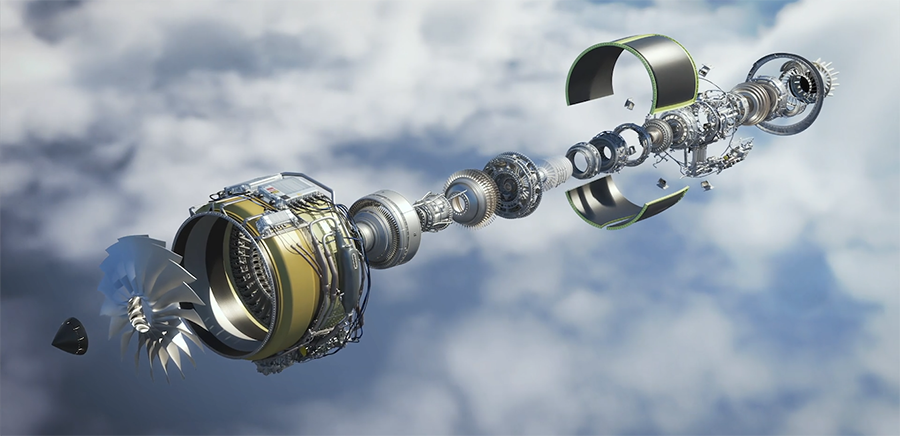

The race to decarbonize flight just picked up speed. Airbus and CFM International said this week they’ll collaborate on tests of an aircraft engine fueled by hydrogen.

As races go, this is a long-distance one. The partners will go to work immediately, with the aim of performing the first tests around the middle of this decade. This demonstration could pave the way for an aircraft that, if all goes according to plan, would carry passengers in the mid-2030s while producing no carbon emissions during flight.

When Mimmo Catalano was 5 years old, his dad took him to work at his office, at an airport in Sardinia, and the boy’s imagination was captured. Today Catalano is a 16-year veteran of Etihad Airways, and last October he captained a long-haul flight from London to Abu Dhabi that was like none before it. The Boeing 787-10 Dreamliner, powered by GE Aviation’s GEnx engines, produced carbon emissions 72% lower than those on a typical flight.

Last October, NASA and GE Aviation announced a new partnership to mature a megawatt-class hybrid electric engine that could power a single-aisle aircraft. Today the project got one step closer to takeoff. GE Aviation has selected Boeing to modify the plane that will test the propulsion system in the air.

Some big ideas begin their life as a sketch on a napkin. You might say that a recent commercial flight that could help the aviation industry reduce its carbon footprint had only a slightly less humble beginning: It popped into existence as a PowerPoint slide during a video call.

After leading Secretary Tom Vilsack on a tour of the engine development assembly facility at GE Aviation’s headquarters in Evendale, Ohio, in early December, chief engineer Chris Lorence posed a rhetorical question to the reporters assembled for a news conference: “What does the Department of Agriculture have to do with aviation?”

A lot, it turns out.

Mimmo Catalano still remembers his first business meeting. It changed his life.

He was only 5 years old when his father, who worked for an Italian airline, took him to his office at the airport. “That day I saw airplanes for the first time, and I loved them immediately,” he says. “From them on, I kept asking my father, ‘Hey, are you having a meeting at the airport? I want to come with you.’ It was love at first sight.”

From the outside, there’s nothing unusual about the Boeing 737 MAX 8 jet operated by United Airlines that flew from Chicago’s O’Hare to Washington’s Reagan National Airport with 115 people on board yesterday. But the plane made history. It was the first commercial flight with passengers on board to use 100% drop-in sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) for one of the aircraft’s two engines.

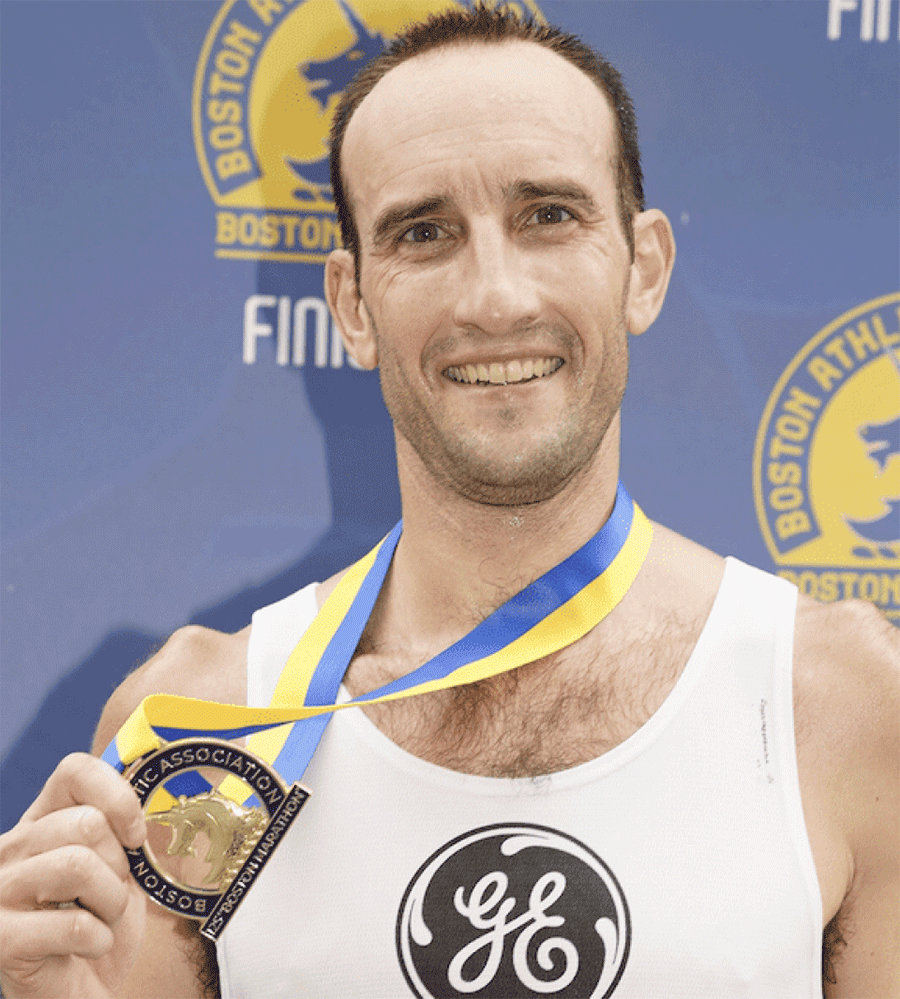

Engineer and avid runner David Riddle usually finds himself asking “Why do I do this” during races. But this year’s 125th running of the Boston Marathon was an exception.

That’s not to say that it wasn’t hard or that it didn’t hurt. It did. But everything was going according to plan. A rarity in distance running. While Riddle has run upwards of 10 marathons, many more 50K+ races and even two 100-plus-mile races, this was his first Boston Marathon.