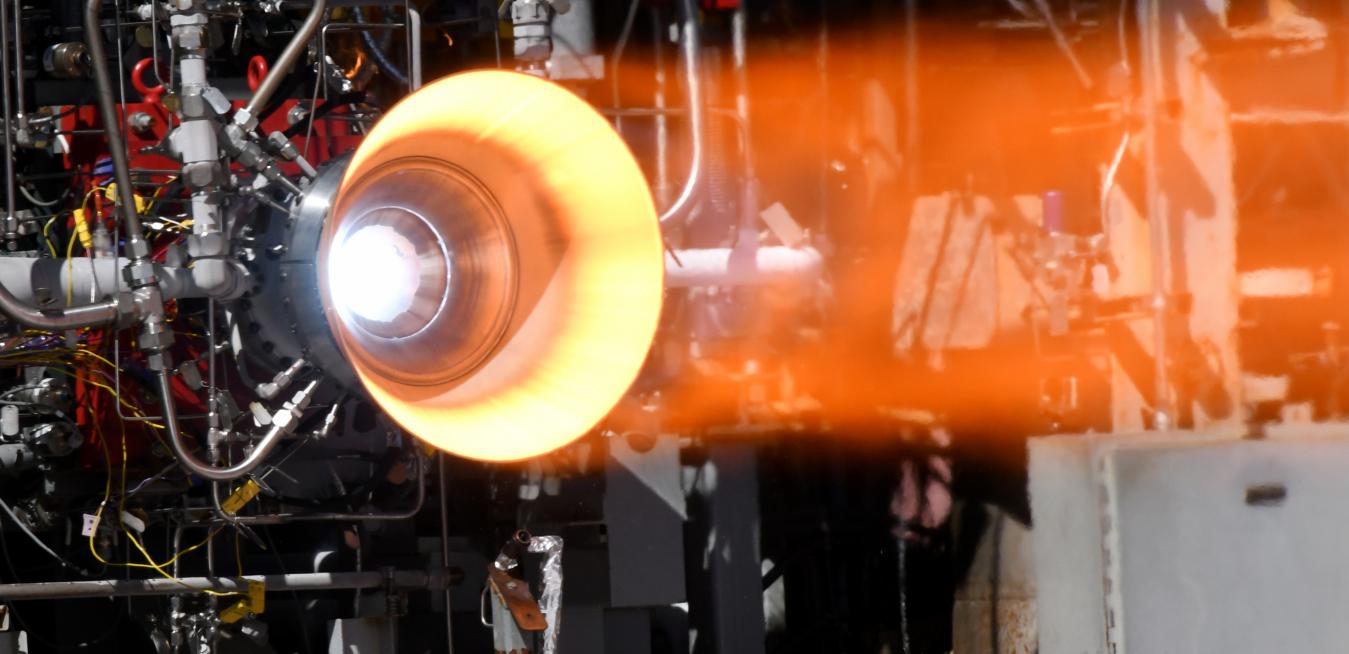

When Christopher Protz and Paul Gradl first started experimenting with building rocket engine components out of copper, the NASA engineers feared they might be wasting their time. Back in 2014, copper had never been used in 3D printing, and it appeared ill-suited to the technology. For one thing, particles of the shiny metal had a nasty habit of directly reflecting the 3D printers’ laser beams, partially melting the copper while frying some very expensive lasers. Early prototypes, recalls Protz, came out looking like “dark-colored blobs.”

Jet engines are large and complicated machines. But sometimes surprisingly small parts can make a big difference in how they work.

A decade ago, engineers at CFM International, a joint venture between GE Aviation and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines, started designing a new, fuel-efficient jet engine for single-aisle passenger planes — the aircraft industry’s biggest market and one of its most lucrative.

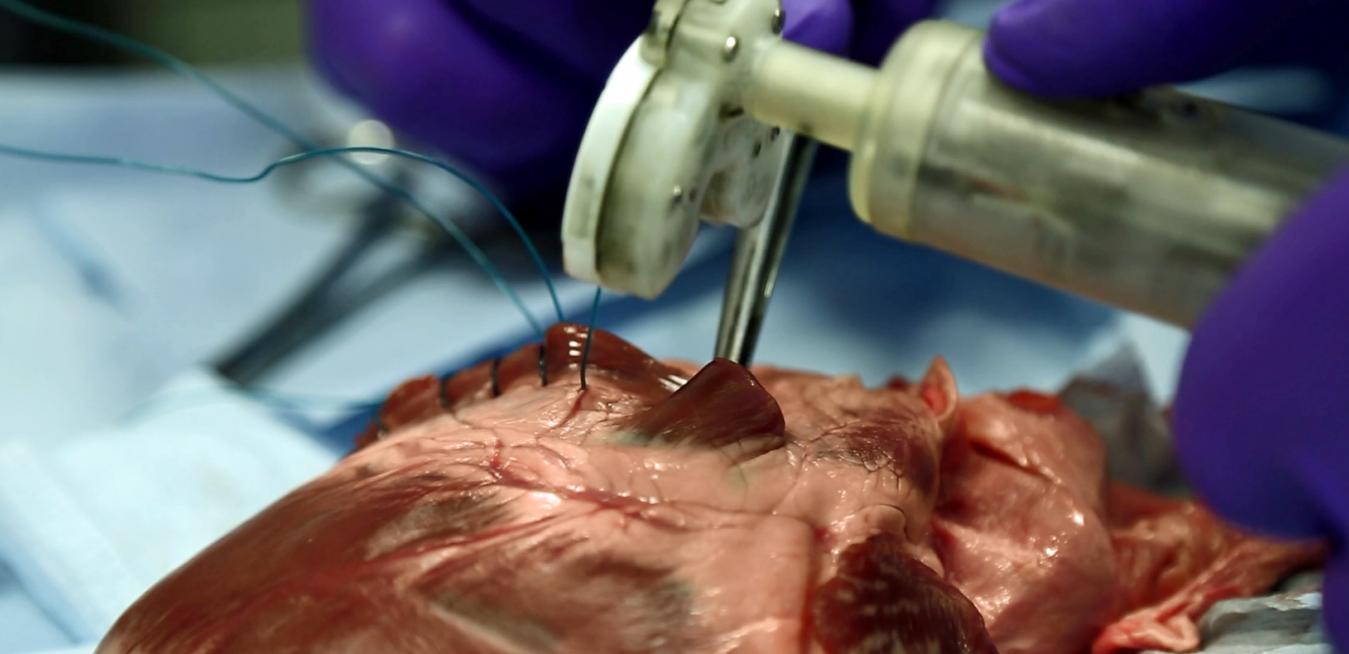

At first glance, the line of cheerfully colored plastic skulls atop professor Laurent Lantieri’s bookshelf might be out-of-season Halloween decorations. But a closer look reveals something less than cheery: jagged holes, missing jaws and crumpled eye sockets. The skulls represent something very real — injuries that Lantieri has fixed.