For the first time in more than 100 years, the global energy landscape is undergoing a massive transformation. The way we generate, transport, distribute, and consume electricity will change more in the next 10 years than it did in the previous 125. What was once an orderly, monolithic system pushing power out to the people, the electric grid is transforming into a two-way highway of energy from diverse sources — including wind and solar — which present new challenges to grid stability and reliability.

In 2020, GE made a commitment to become carbon-neutral in its own operations by 2030, and the following year the company announced that it is going even further, reaching net zero by 2050 — including the Scope 3 emissions that result from the use of sold products. As the company unveiled its 2021 Sustainability Report this week, we looked back at some of this year’s biggest developments, which include offshore wind, hydrogen fuel, carbon capture and sequestration, small modular nuclear reactors, pumped hydro and other technologies.

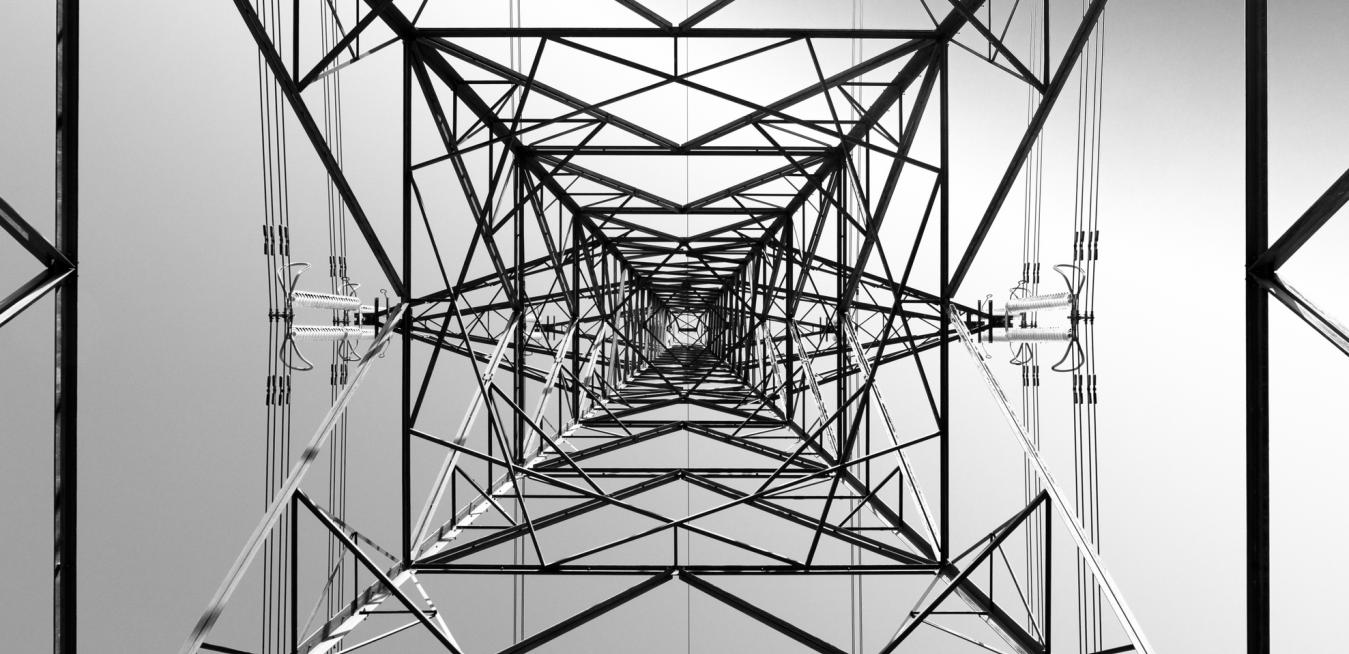

We may take it for granted, but the electrical grid is one of the most remarkable systems around, sending electricity through thousands of miles of power lines into millions of homes and charging up billions of devices. Traditionally, it’s also been a centralized system, where the hub of a power plant pushes out energy into the spokes toward every end user. Climate change means that has to change, though — and in ways you may not expect.

It’s small, aluminum and barely larger than a hardcover book. But just like the dial-up modem a few decades ago, the device is helping revolutionize electrical power in ways we haven’t seen before.

A mass of electrical cables may look like spaghetti to many people, but Nicolas Godingen has become an expert at picking each strand apart in his mind’s eye.

Nearly every day, the field service manager for GE in Singapore gets messages and calls from engineers who need quick guidance on emergency repairs at, say, a substation supplying electricity to an airport. Or they might ask for help with an issue affecting the national power grid.

When Thomas Edison switched on the first electrical grid in downtown Manhattan in 1882, the project was a great engineering feat as well as a brilliant marketing ploy. Starting small, his grid covered just a few blocks of New York City’s financial district serving some very influential customers. This first step unleashed a tsunami of innovation and growth the same way the Internet would a century later, but years later its evolution slowed to a crawl.

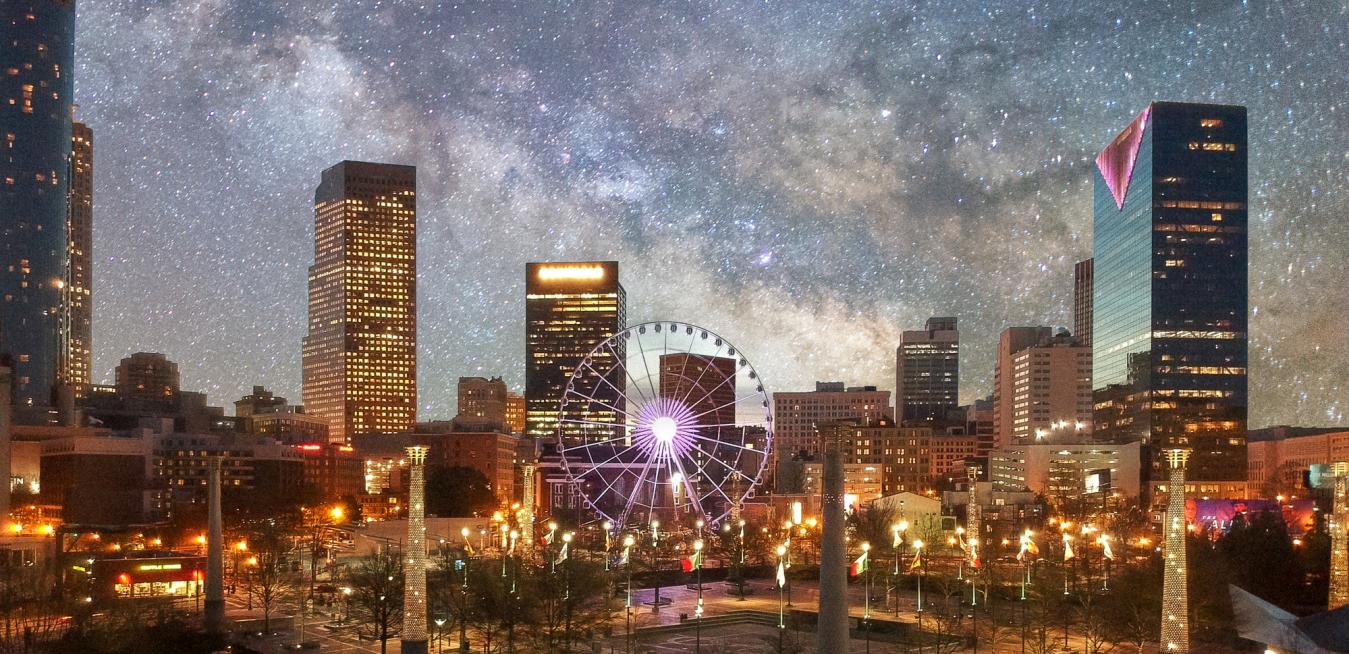

On Dec. 27, 2018, a loud boom rousted New Yorkers from their holiday revelry. While Christmas tree lights flickered inside, a scene straight out of “Ghostbusters” was unfolding outside. A canopy of smoke-tinged electric blue cloaked a section of the night sky, and Twitter exploded with photos, videos and speculation: Had aliens landed in Queens? Was the city under attack?

Electrical substations — the clusters of circuit breakers, transformers and switchgears that stick out of the ground like giant cattle prods — aren’t much to look at. What they lack in glamour, they make up for in sheer utility. Substations are the grid’s unsung heroes that toil in obscurity to keep our homes lit and phones charged. You might find one near a power plant, switching up the power generated by, say, a gas-burning facility into electricity that flows in high-voltage transmission cables to towns and cities.