For most people, a half-second delay is something to shrug off. For Steve Reed and Trent Lester, a blip that small might raise a red flag in their safety-focused industry. They work at the Subaru factory in Lafayette, Indiana, the company’s only facility outside of Japan and one of the world’s most advanced automobile plants, where each year more than 6,000 people produce up to 400,000 Legacy, Outback, Impreza, and Ascent models. Reed and Lester collect thousands of data points every second, from the status of air compressors to the amount of antifreeze that’s dispensed into each vehicle.

It’s not hard to imagine a future where every home has an electric vehicle, solar panels on the roof, a battery system in the garage and multiple smart home devices like a connected thermostat or hot water heater.

This vision may still be a few years away, but the energy industry is making sure it’s ready. Power operators have already coined their own jargon for this technology: distributed energy resources, or DERs.

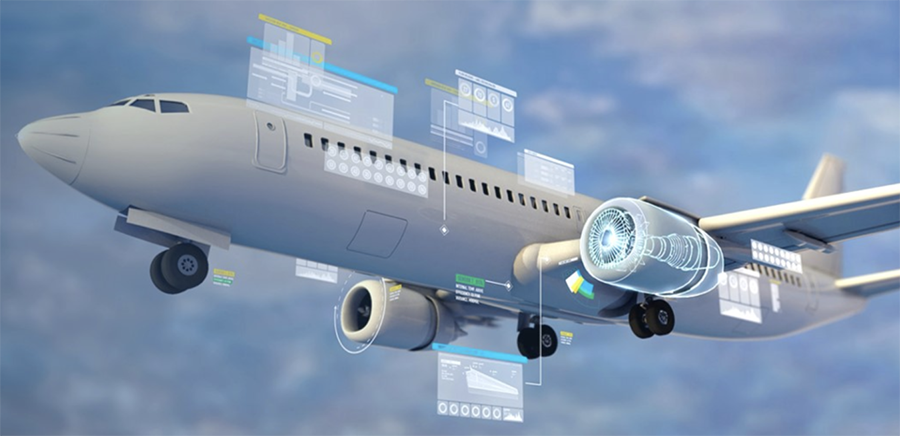

Qantas pilot Captain David Summergreene has spent a quarter of a century flying passenger jets around the world. But his epiphany came while he was sitting at his desk and staring at rows of numbers on a computer screen that illustrated how the Australian national carrier was using jet fuel. “For the first time, I was able to self-service as a pilot to look at some of the most interesting metrics to me, rather than having to go to an analyst and ask, ‘Can I have this information, please?’” he says. “I was just overwhelmed by this; I was like a kid in the candy shop.”

The energy transition to renewable electricity is gathering speed, with wind farms and solar panels popping up around the world. While renewables help us cut carbon, they have their own challenges. In the absence of grid-scale storage, what happens when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine? The good news is that there are people like Jim Walsh, general manager of the grid software business at GE Digital, who are working on the problem and helping grid operators make sure that our power doesn’t go out. “This problem is way too big for paper and a pencil,” Walsh says.

Last November, a long-haul flight from London to Abu Dhabi operated by Etihad Airways notched an important aviation industry milestone by reducing the trip’s carbon emissions by 72% compared with an equivalent flight in 2019, using existing technologies.

GE Digital’s thousands of customers are among the best-known brands in the world, including Procter & Gamble, Subaru, Qantas and Southern California Edison. In each case, GE Digital’s teams are helping to transform and speed up how those companies use data to help their operations — call it the industrial internet. Now GE Digital has a new leader: Scott Reese, an executive at Autodesk, will become chief executive officer effective Feb. 22. He replaces Patrick Byrne, who will continue at GE as chief executive officer for the Onshore Wind business at GE Renewable Energy.

Data may not be what makes the world go round, but it can help airlines increase fuel efficiency and, by extension, help reduce carbon dioxide emissions when their passengers are on globe-trotting adventures.

Earlier this week, GE announced a “defining moment” in its history, a plan to form three global public companies, each a leader in its industry, focused on aviation, healthcare and energy.

In the 1970s, a team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology traveled to Japan to figure out why that country’s automakers were delivering cars faster than their competitors in Detroit. Their search led them to Toyota and its Toyota Production System — a set of management principles focused on boosting safety, quality and efficiency, reducing waste and creating more value with fewer resources.