A mass of electrical cables may look like spaghetti to many people, but Nicolas Godingen has become an expert at picking each strand apart in his mind’s eye.

Nearly every day, the field service manager for GE in Singapore gets messages and calls from engineers who need quick guidance on emergency repairs at, say, a substation supplying electricity to an airport. Or they might ask for help with an issue affecting the national power grid.

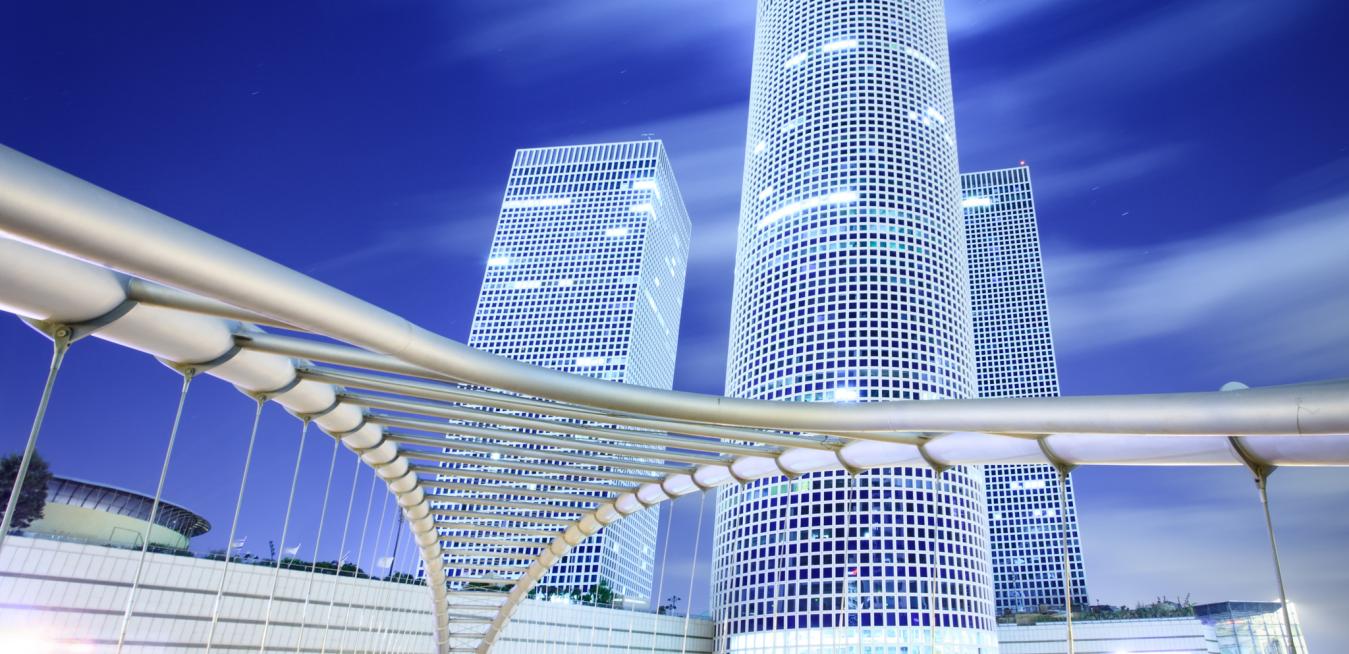

Located on a narrow strip of land bookended by the sea on one side and desert on the other, Israel, like many countries, is raising an alarm about climate change.

At precisely 8:30 p.m. on Friday, May 24, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pressed a Western Union telegraph key in the White House and an electric pulse traveled 500 miles over copper wires to a signal lamp near first base at Crosley Field in Cincinnati.

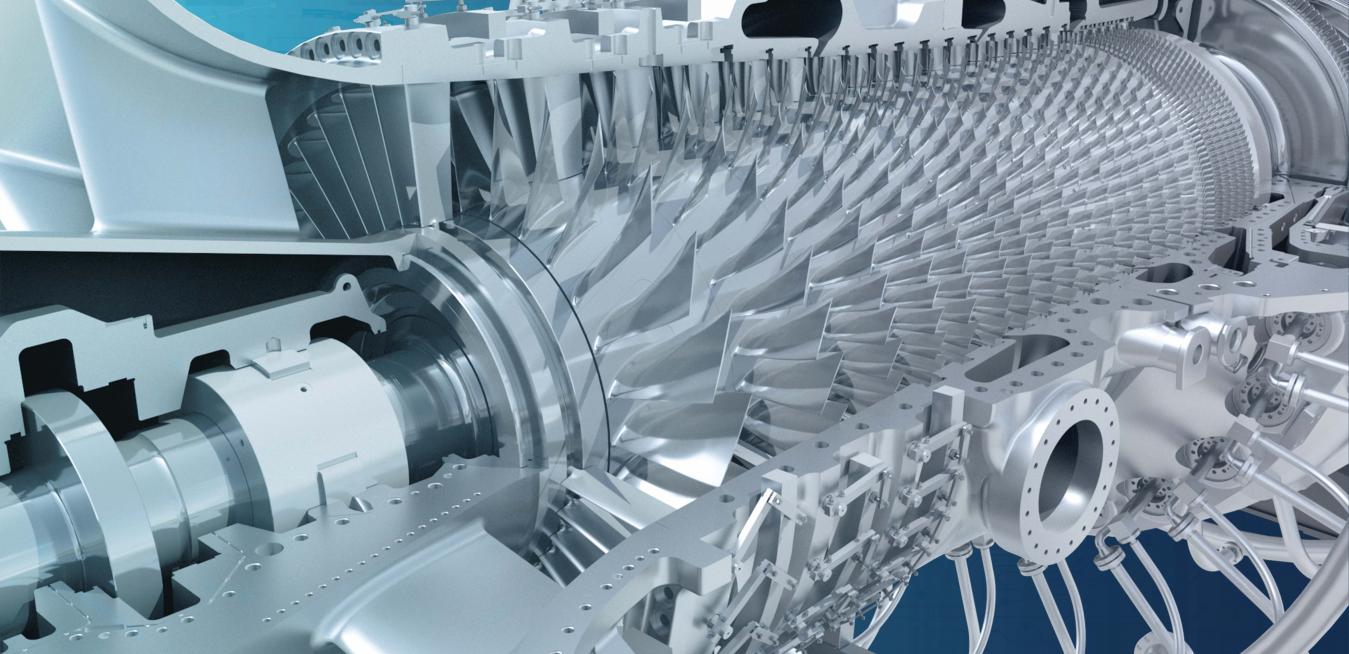

The growth of renewable power means that the owners of the world’s gas turbines have to accept some Darwinian logic: Adapt or die. The challenge is particularly acute in the U.K., where electricity production from wind, solar and hydropower installations is booming. The total installed capacity of the country’s renewables sector now exceeds that of fossil-fuel-fired generation, or power plants that burn coal, gas and oil.

The Ostroleka C power station, currently under construction in Poland, could be the last coal-fired power plant built in the European Union country. But that hardly means the technology inside it has no future.

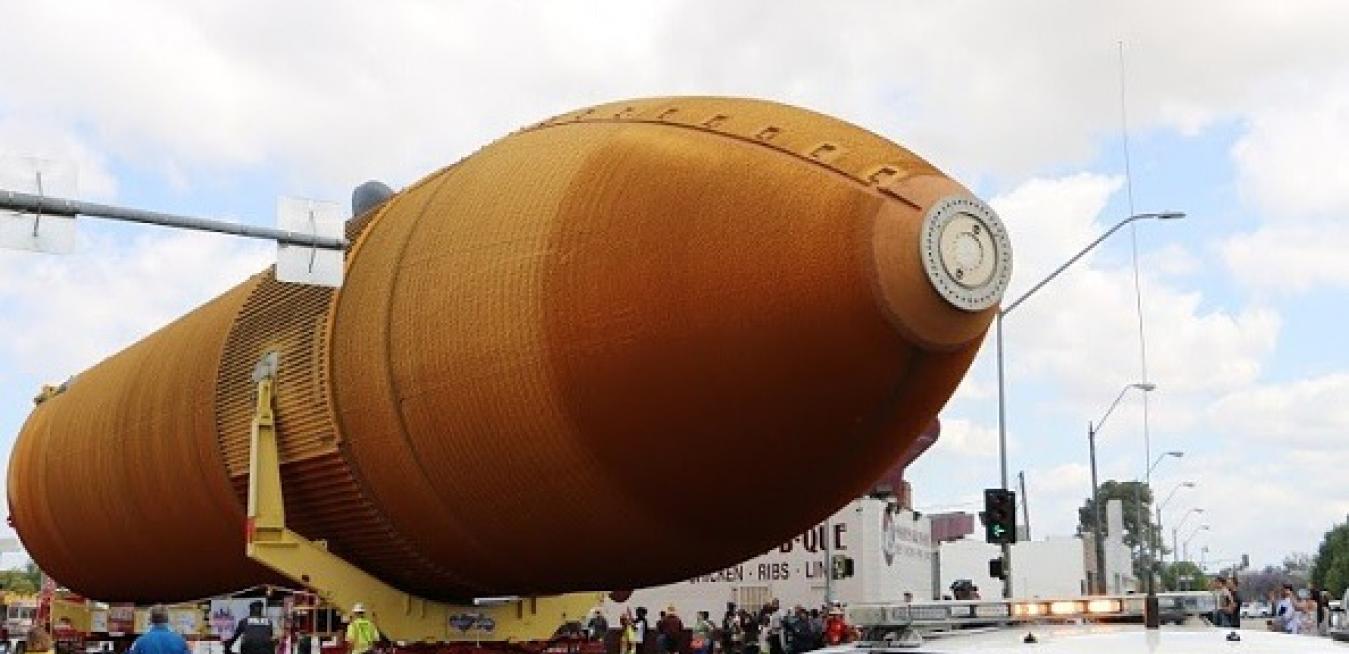

If you studied chemistry in school, the memory of hydrogen will be a blast from the past — literally. You can’t see or smell hydrogen, but you know it’s there when you hear a squeaky pop when holding a lit match above the test tube. Hydrogen’s easy flammability and unparalleled lightness make it easy to understand why NASA uses it as rocket fuel. (It also happens to be the most abundant element in the universe.)