Hutchinson, who was 58 at the time, didn’t regain control over her hands. She did it by moving a robotic arm with her thoughts.

Like microchips inside computers and laptops, power management chips are pieces of semiconductor as small as a cornflake. But they move electricity (watts), not data (bytes). Their circuits help extend battery life and reduce power consumption for a broad range of devices: from smartphones and tablets to brain scanners and jet engines. They can make machines smaller, lighter, and more efficient.

What comes to mind when you think about a canoe? William Clark and Meriwether Lewis paddling down the Columbia River? Summer evenings spent on a lake at camp?

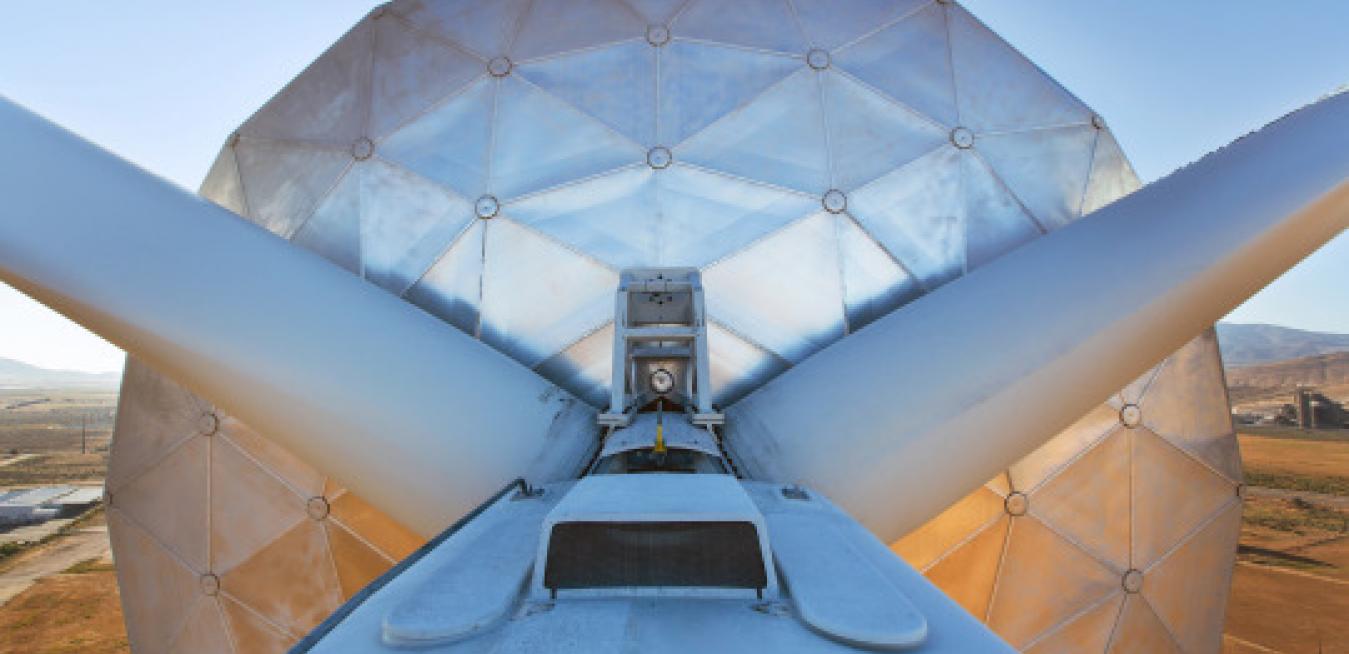

When a blast of icy weather hit a Canadian wind farm two winters ago, its chill lingered a month. The storm covered almost three dozen wind turbines with ice and they had to shut down. “The cold weather [was] not an issue,” the farm’s manager Mark Hachey told CBC News. “They can run in rain, they can run in snow. It’s when you get an accumulation of ice, much similar to an airplane.”

Two things lurk deep at the heart of the digital love story. It’s not “me” and “you.” It’s “0” and “1.”

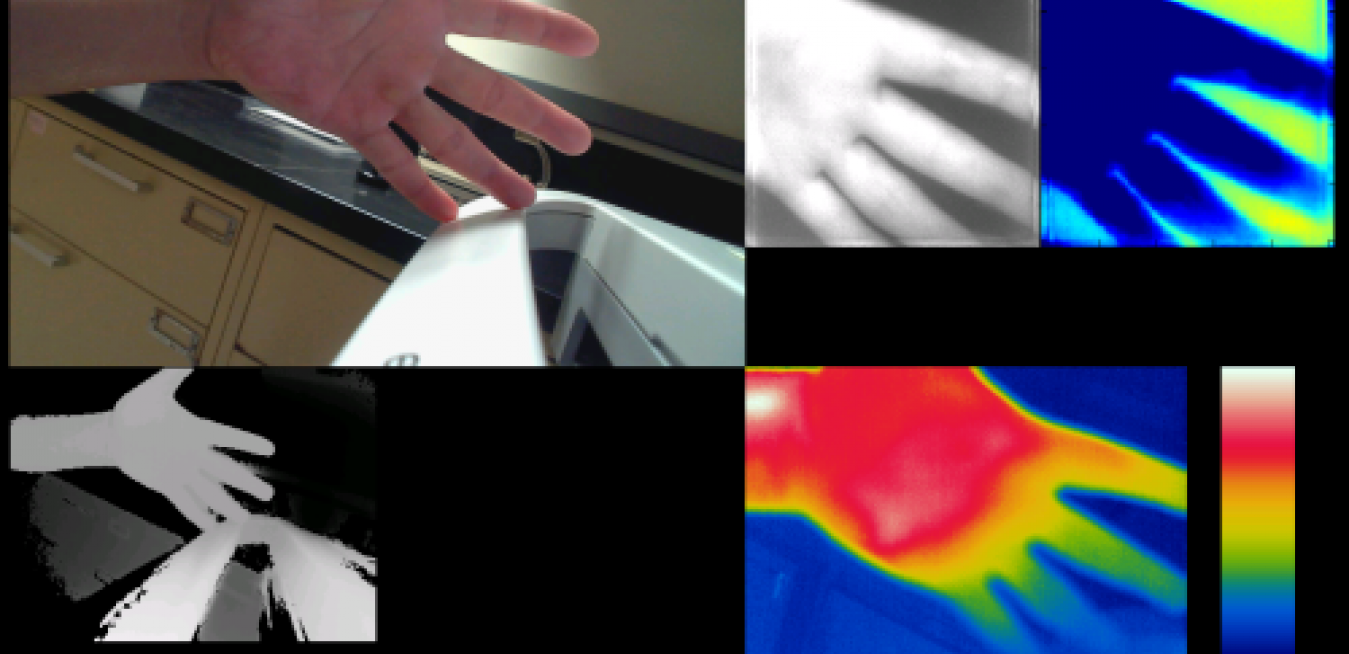

The analytics that are helping people find a better match are just one place where science informs contemporary life. Big Data may be unromantic, but it’s powerful and efficient. It’s helping wannabe lovers as well as scientists to find new meanings and hidden patterns in piles of data and build better robots, decode the brain, and, yes, avoid a bad first date.

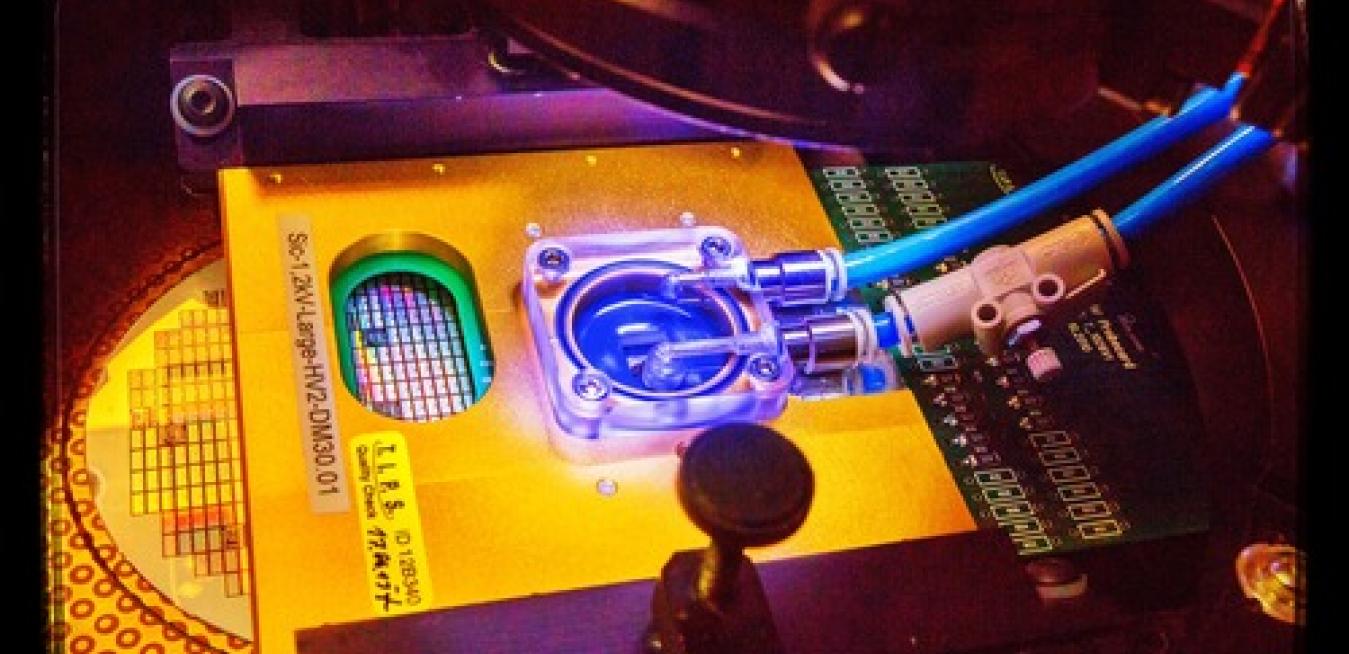

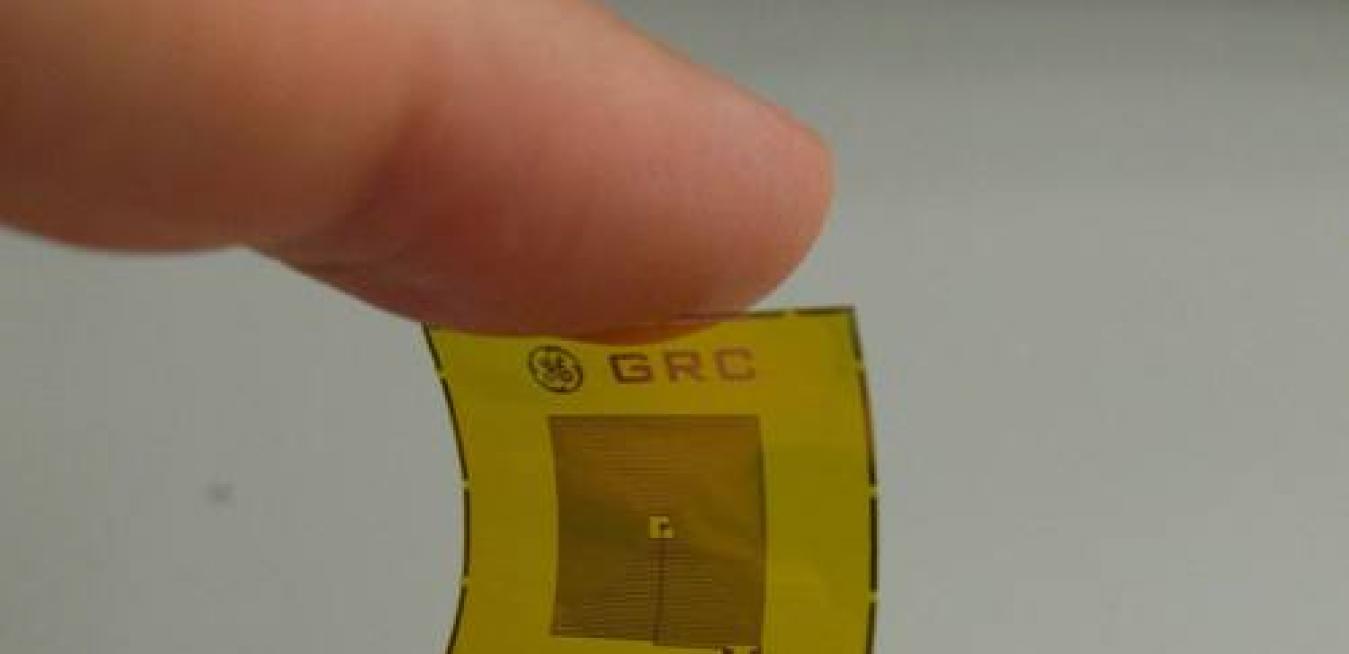

Engineers in GE labs have built a penny-sized radio sensor that can detect the faintest traces of chemicals and explosives and needs only a tiny amount of power to operate. The device uses a special film a tenth the thickness of a human hair to spot the compounds.