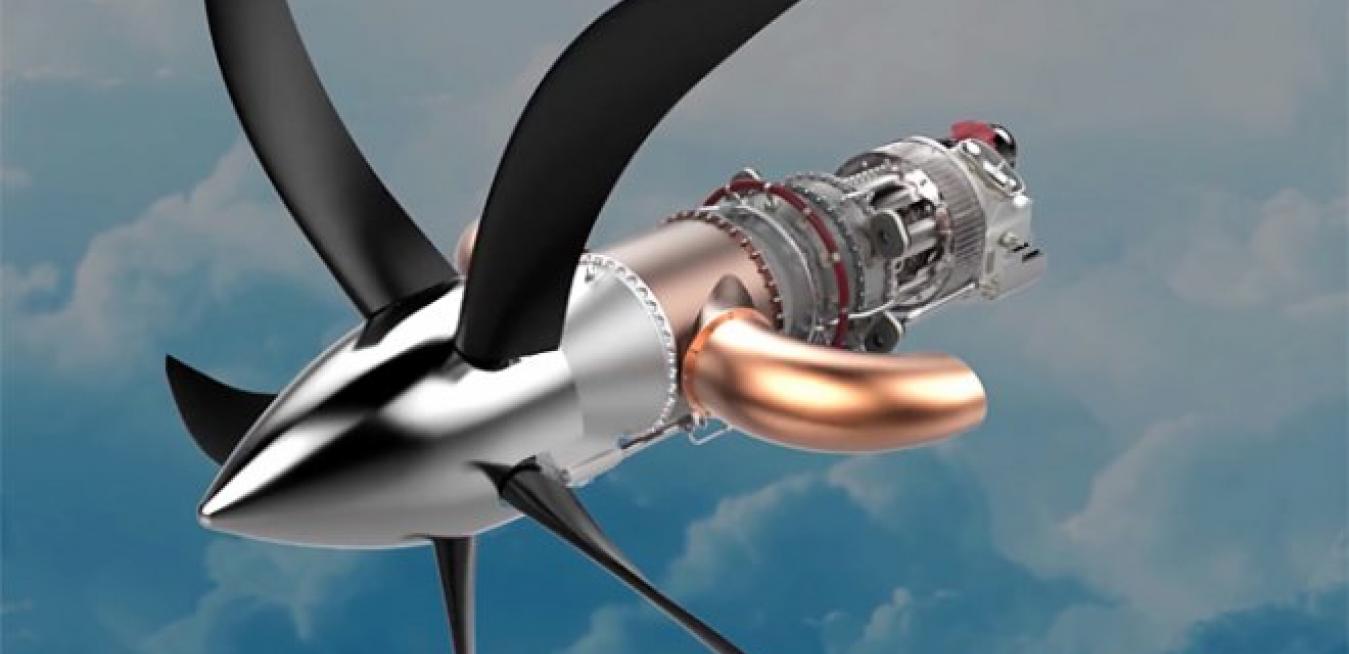

Nestled in the rolling hills of the Po Valley, the small town of Cameri looks like a postcard Italian village, complete with a classic piazza surrounded by traditional-style buildings and a church. It’s a startling contrast, then, that less than a mile from the center of this village sits a major hub of aerospace innovation, anchored by one of largest 3D-printing factories in the world. Operated by Avio Aero, a GE Aviation company, the plant makes the arm-sized blades for the GE9X engine, the world’s largest jet engine.

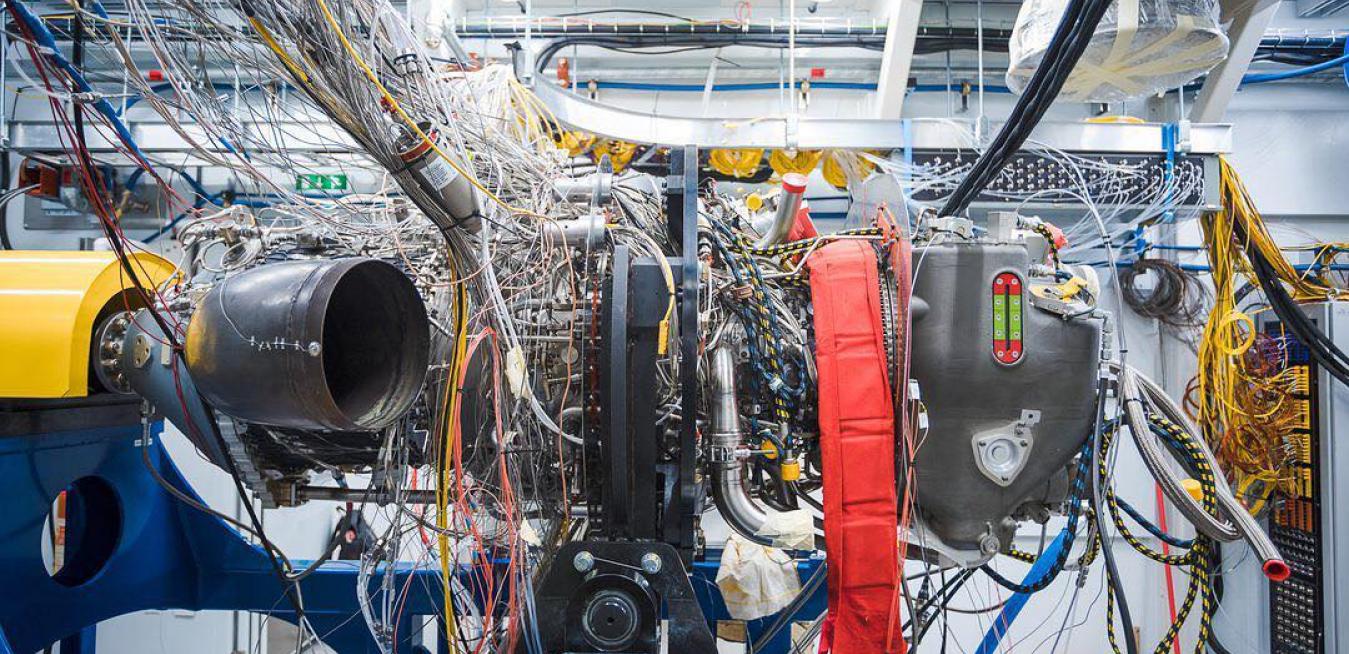

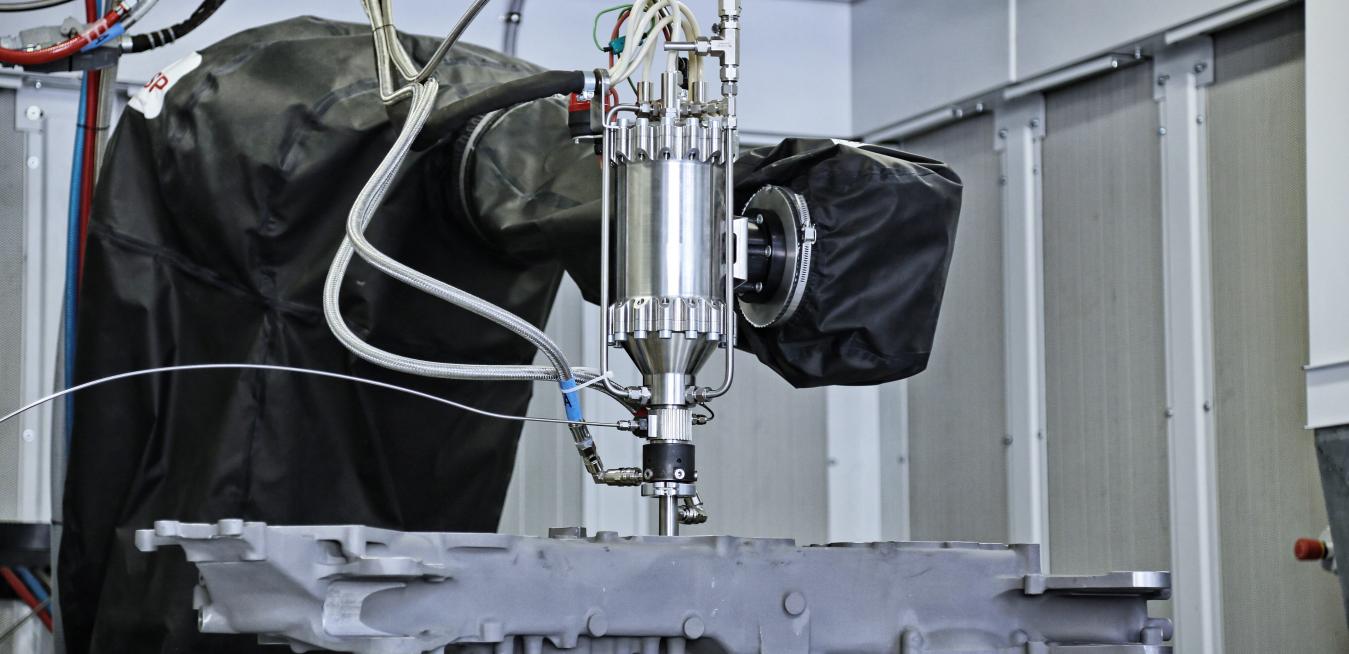

When you first see it, GE’s new Catalyst turboprop engine looks a little like a piece of captured alien technology. Strapped to a metal bed inside a concrete hangar on the outskirts of Prague, the gray metal machine bristles with some 500 silver cables connected to external and internal sensors.

Lucca, a sandy-colored, 1-year-old shih tzu, is undeniably cute — thanks in part to the tiny legs he trots about on. But one of those legs was also a source of potentially lifelong discomfort for the pup. Lucca grew up with a deformed lower leg, a condition often found in smaller dogs, including shih tzus and dachshunds: Two bones in his front right leg developed at different rates. When one stopped growing prematurely, it acted like a bow string, causing the other to twist and bend.

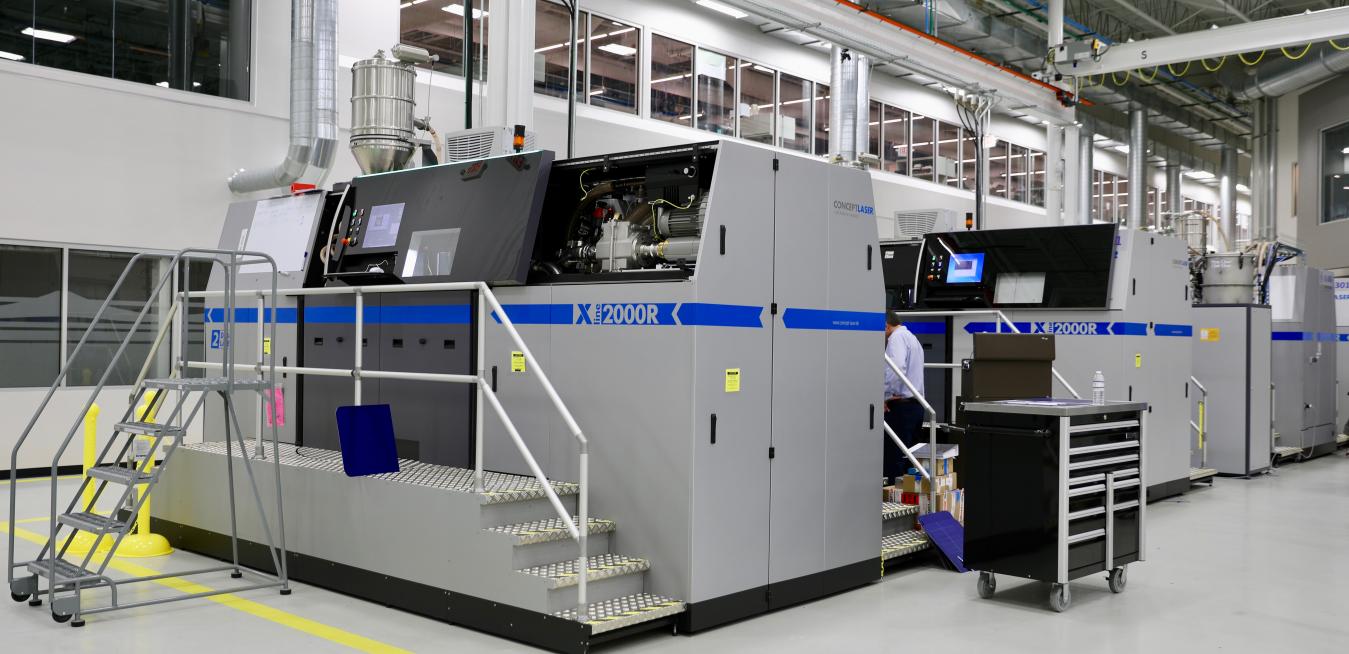

Mark Twain allegedly claimed that when the end of the world came, he wanted to be in Cincinnati “because it’s always 20 years behind the times.” The quip is funny, but his strategy to ride out Armageddon in the Queen City would backfire today. A case in point is GE’s Additive Technology Center located along Interstate 75 as it bisects the northern suburb of West Chester Township. From the outside, the building looks like many of the low, gray boxes in this industrial area.

3D printing has rightfully gotten a lot of buzz because of the marvels it can do. Also known as additive manufacturing, it has opened new paths for designers to create custom shapes that were previously too expensive or downright impossible to make. The technology's potential is enormous, but GE engineer Peter Martinello offers a dose of perspective. “This is true if you have to print just one part,” he says.

You probably wouldn’t print a letter without carefully composing and editing it on a computer screen first. So it’s fitting that as companies embrace 3D printing, their workers are spending a lot of time on their computers making sure the parts they want to print come out right. And just like writers need a good word processor to keep track of their changes, industrial designers need sophisticated software to run simulations as they perfect their parts.

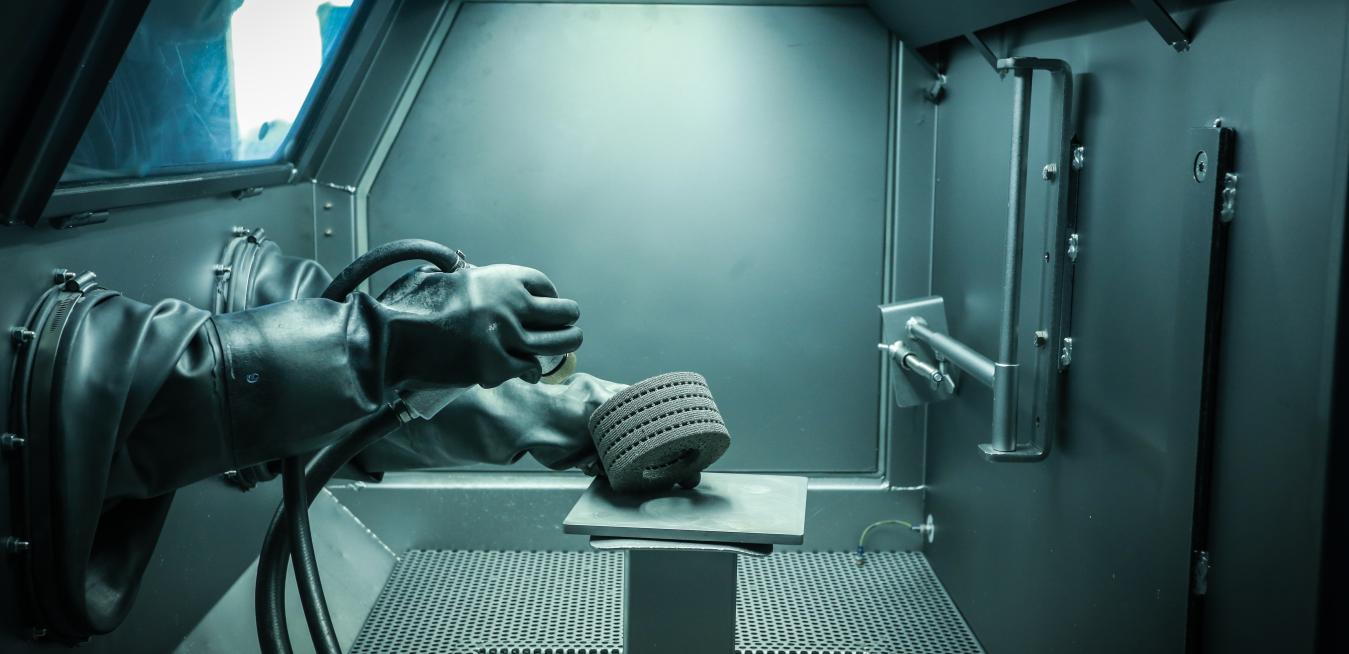

Few places illustrate the rapid evolution of 3D printing better than Avio Aero’s gleaming box of a factory in Cameri, a small town near Milan in northern Italy. The plant is filled with 20 sleek, black 3D printers, each the size of an armoire.