False Positive

In only a few years, a novel genome engineering technology, known as CRISPR, has gone from obscurity to revolutionary. The world is eager to see how this tool could cure a range of deadly genetic diseases. Eyes remain fixated on grandiose headlines, but the public may not be aware of the long road ahead for CRISPR clinical trials, writes Kevin Doxzen of the Innovative Genomics Institute. He explains what needs to happen before CRISPR will make it into your local neighborhood hospital.

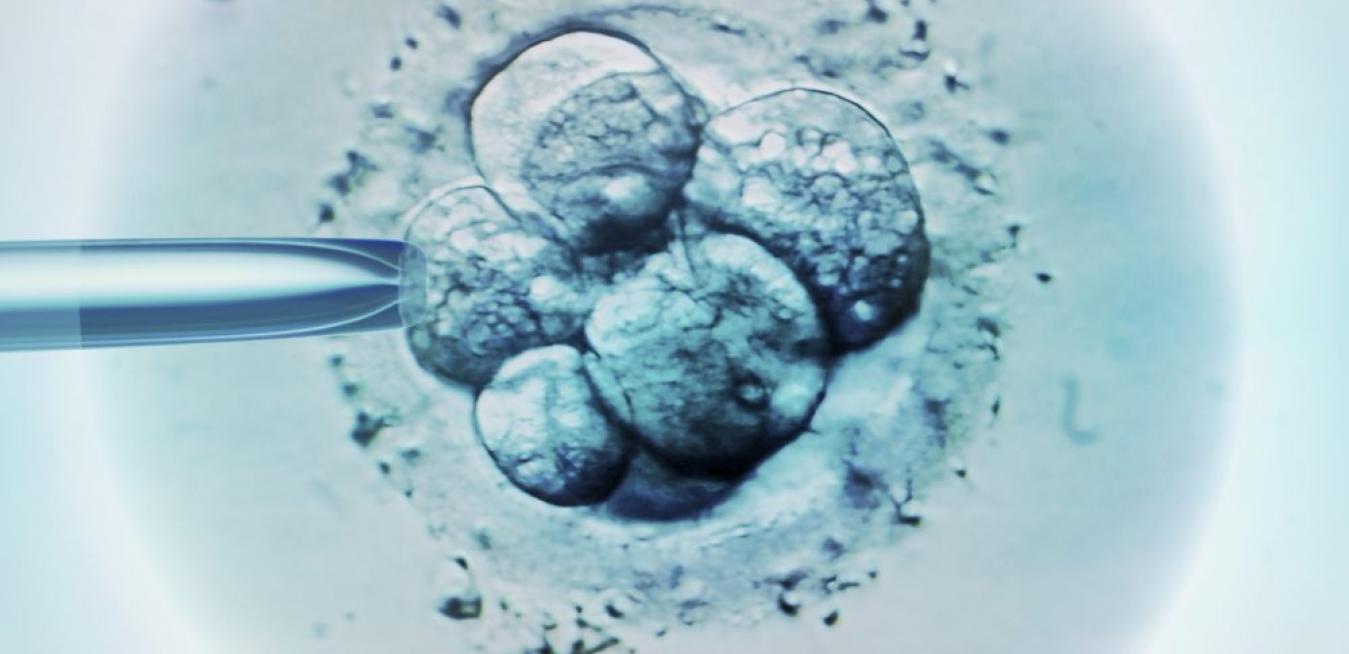

There’s still a way to go from editing single-cell embryos to a full-term "designer baby." But researchers at Oregon Health and Science University say they worked with single-cell embryos, inserting CRISPR chemicals at the time of fertilization.

The announcement by researchers in Portland, Oregon that they’ve successfully modified the genetic material of a human embryo took some people by surprise.

Manipulating our genetic code with CRISPR may be a controversial topic, but it offers scientists the chance to work with the public to shape the ethical future of this technology, writes Megan Hochstrasser of the Innovative Genomics Institute.

Our DNA, the double-stranded helix responsible for heredity, contains 3 billion letters that dictate everything from hair and skin color to blood type. In fact, DNA is the most important identity document we will ever carry. Besides random mutations and damage, it doesn’t change from the day we’re born.

By 1970, cancer was terrorizing almost every American family as it inflicted terrible suffering and for most patients an almost certain death sentence. Its solution was either unknown or, when known, associated with dire consequences. Cancer’s toll on society went beyond human suffering to threaten economic disaster.