Blowout preventers, or BOPs, are incredibly complex machines that sit deep on the sea floor and serve as the last line of defense if something in the oil well goes wrong.

These 250,000-pound, 60-foot steel behemoths have to be regularly pulled up, inspected and serviced. As a rule of thumb, workers often replace as many as 20 percent of their parts to keep them safe, effectively rebuilding the entire machine every five years. “That’s one way to do it,” says Bob Judge, director of product management at GE Oil & Gas.

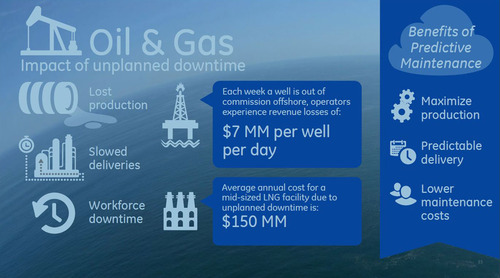

The other, smarter way involves connecting BOPs to the Industrial Internet, and collecting and analyzing the data they send up. “We need to move from the ‘break-fix’ model to a predictive maintenance model,” Judge says. “What if you had a technology gathering BOP data so that the next time you pull it out you know exactly what needs to be replaced and have the replacement parts available on the drilling rig?”

Judge says that it costs between $10 and $16 million to surface a BOP. Predictive maintenance could save drilling companies millions in unplanned downtime.

He compares such systems to the oil life indicator in a 2014 model car. “Not so long ago, you changed your oil every 3,000 miles,” he says. “But a new Chevy Tahoe will tell that you have 27 percent of oil life remaining, based on mileage and other engine conditions that affect the oil. That’s predictive analytics.”

Judge and his team spent the last couple of years studying BOPs and data about wellbore and hydraulic system pressures, solenoid current draws, valve positions and other information. The data is already being supplied by sensors on BOPs and stored in a database called “datalogger.”

They used the data to develop a system called SeaLytics BOP Advisor that allows crews to monitor the health of BOP components and determine how many cycles they have gone through, what needs to be fixed and when. “When there is a problem, the drilling contractor will know within seconds,” Judge says.

The technology is similar to GE systems that already monitor jet engines and locomotives. It is built on Predix, the first industrial-strength platform built by GE for machine analytics.

Judge said that he had an epiphany for SeaLytics when he saw a demonstration of myEngines, which allows airlines to remotely monitor the status of their jet engine fleets and streamline maintenance and repair. “I thought if we could have the same model that’s been proven to work to benefit the drilling industry,” Judge says.

Two customers, the drilling contractors Atwood Oceanics and Brazil’s Queiroz Galvão Óleo e Gás (QGOG), already ordered the technology. “Telling a customer what to fix after it has failed is relatively easy,” Judge says. “Telling them to fix something before it costs them money is the magic.”