This summer, employees at GE Aviation gathered for a festive celebration outside the GE unit’s global headquarters in Evendale, Ohio, just north of Cincinnati. The star of the party was a massive jet engine — its front fan alone spans more than 11 feet in diameter — that GE developed for Boeing’s next-generation 777X widebody jet. The occasion? The engine, called GE9X, achieved 134,300 pounds of thrust during testing, making it the most powerful jet engine on the planet.

The huge engine stands on the shoulders of a much older machine: the very first U.S. jet engine, which GE engineers started building in Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1941. The GE facility where the celebration took place is also steeped in aviation history. Together, the jet engine and the factory would go on to define the future of GE Aviation, which is celebrating 100 years in 2019. They would also help chart the future of the entire aviation industry.

On June 12, 1941, 900 miles from Lynn, a diminutive man with white hair and a white mustache drove alone from his mansion near downtown Dayton to the massive Wright Aeronautical piston engine factory about an hour away, near Cincinnati. He came to witness the new complex’s grand opening. Known then as the Lockland Plant, it was one of the country’s largest and most modern defense factories, even though the United States was still months away from joining the Allied war effort.

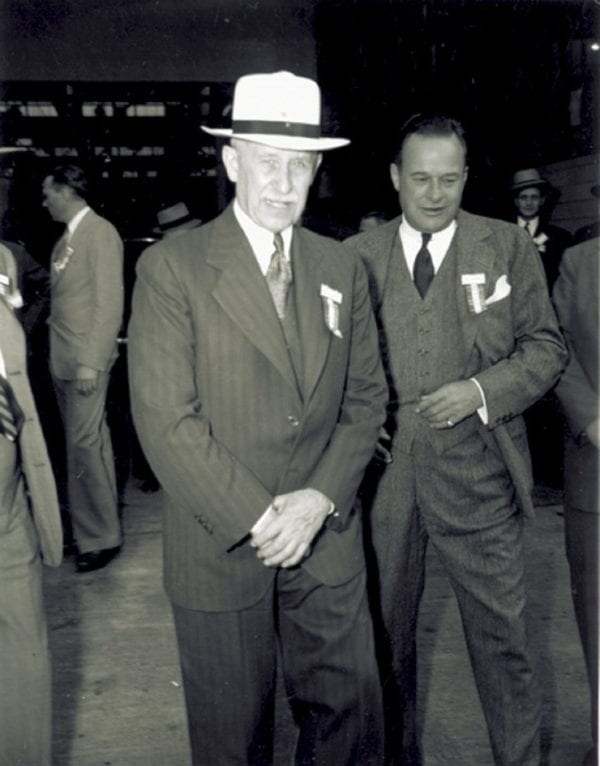

Looking sporty in his suit and Panama hat, the elderly gentleman arrived early at the badging area, where he quickly made the rounds, shaking hands and chatting with Wright Aeronautical executives and local dignitaries clearly thrilled to meet him. With good reason: His name was on the company they had assembled to honor.

The man was Orville Wright. Only 38 years earlier, he and his brother Wilbur had introduced powered flight to the world. Wilbur died in 1912; four years later, Orville sold their airplane company to the Glenn L. Martin Company of California. The merged entity was eventually swallowed up into the massive Curtiss-Wright Corporation, which operated a Wright Aeronautical division as a world-leading producer of piston engines.

Above: Orville Wright’s comments during the ceremony inspired headlines around the world. Image credit: Special Collections and Archives, Wright State University. Top: American aviation pioneer Orville Wright (1871 - 1958) sits in one of his biplanes in Dayton, Ohio. The image was taken around 1909. Image credit: American Stock/Getty Images.

Above: Orville Wright’s comments during the ceremony inspired headlines around the world. Image credit: Special Collections and Archives, Wright State University. Top: American aviation pioneer Orville Wright (1871 - 1958) sits in one of his biplanes in Dayton, Ohio. The image was taken around 1909. Image credit: American Stock/Getty Images.By 1941, Orville, who never married, had largely withdrawn from public life. At 69, he spent his days tinkering in his small “laboratory” on Dayton’s West Side, in the same neighborhood where he and Wilbur first invented airplanes. Orville was soft-spoken and reserved, but he was not a recluse; he made a point of attending events that celebrated him or marked significant aviation milestones.

The Wright Aeronautical grand opening was one such occasion. On the eve of America’s entry into World War II, the new factory complex was billed as an industrial wonder. In the ensuing years, the complex would produce piston engines for the C-47 transport as well as B-17 and B-29 bombers. The complex was shuttered within weeks of the war’s end, and GE took occupancy three years later.

For decades, urban legend had it that Orville got lost that day, wandering through what GE calls Building 700 — once heralded as the world’s largest single-story building — and delayed the Wright Aeronautical ribbon-cutting ceremony. That is likely a myth. By all accounts, Orville’s fascination with the long assembly lines of Wright Cyclone pistons slowed up the formal tour organized for him and area reporters. This briefly delayed the festivities.

While not physically lost, Orville did appear to get lost in his thoughts. Though he never spoke during the formal ceremony, his offhand comments to reporters caused headlines across the country. In one news account, Orville whimsically caressed the cylinder heads of a 1,700 horsepower piston engine and remarked, “Just to think, Wilbur and I flew behind a little thing [engine] of four cylinders that developed all of 40 horsepower, maybe 44.”

Then he grew serious: “In a sense, I guess we didn’t know what we were doing when we built our first plane. We never envisaged a plane as a terrible engine of war, certainly. But there will always be someone who will abuse anything. That has always been my answer when people ask whether I would have attempted our early experiments had I been able to foresee all of the terrible destruction that has come from the air.”

His comments inspired sensational newspaper headlines across the country: “Inventor of Plane Saddened Because World Misused It”… “Uses Of Airplane Sadden Pioneer”… “Wright Looks Sadly On Use Of Airplane”… “Wright Sad As Airplanes Spread Death”… “Inventor’s Anguish”… “Wright Views Modern Plane With Tinge Of Sadness”… “Inventor Now Views Plane With Sadness.”

The GE9X is the world's most powerful jet engine. Image credit: GE Aviation.

The GE9X is the world's most powerful jet engine. Image credit: GE Aviation.It was not the message Wright Aeronautical hoped to amplify at its grand opening ceremony. The irony is that Orville and Wilbur became wealthy men in 1909 through large U.S. military contracts to produce the Wright Flyer, considered the world’s first military aircraft.

After the event, Orville gave a Dayton reporter a ride home and went back to tinkering in his lab. The Wright Aeronautical plant boomed over the next four years. At peak production, the factory operated around the clock, employing more than 30,000 people and pumping out more than 3,000 radial engines a month. When operations were suspended on August 17, 1945, with the end of World War II, 27,000 employees worked in the complex. Final paychecks were issued a week later, and the massive plant was mothballed.

In early 1948, at age 76, Orville died from heart disease. He had lived long enough to experience the dawn of the jet age. In fact, eight months after his death, GE Aviation employees from the Lynn, Massachusetts, plant began moving into the empty Wright Aeronautical plant in order to produce the GE J47 fighter jet, which would become the most produced jet engine in aviation history.

In the last decade, GE Aviation has invested more than $500 million in the complex. The site, among the nation’s most impressive aviation facilities, has hosted numerous aerospace luminaries over the years, from Charles Lindbergh and John Glenn to Neil Armstrong. But none were more significant than the elderly man from Dayton who arrived in 1941, reflected upon his life and spoke from his heart.

GE found and restored the original tiled mural from the Wright Aeronautical factory. Image credit: GE Aviation.

GE found and restored the original tiled mural from the Wright Aeronautical factory. Image credit: GE Aviation.The Wright legacy has never left the GE Aviation site. About 15 years ago, while tearing down a building on the large campus, workers came across a Wright Aeronautical tiled mural, which originally adorned the floor of the reception lobby. They cut out this historic piece of art, made of terrazzo, from the floor, wrapped it up, and stored away in a safe place.

Earlier this year, after months of restoration, Evendale facility operations leader Tim Meyers and office environments business leader Jennifer Seeling remounted the mural outside where employees could see it. “We have been working to restore this beautiful piece of historic art by stripping it all the way down, filling in the cracks, recoloring it and putting a coating on it to preserve it and bring it back to life,” said Meyers.

“We always thought we were going to put the mural someplace to showcase this piece of history that would keep us grounded to where the original site came from,” he continued. “This piece of floor encompasses the very journey that GE Aviation has been on, and we want to protect that.”

GE has other connections to the Wright Brothers. Jimmie Beacham, chief engineer at GE Healthcare's Advanced Manufacturing Technology Center comes from a family whose members witnessed the first Wright Flyer flights. Beacham’s great-grandfather William T. Beacham (second from left), grandfather John L. Beacham Sr. (the small boy holding his hand) and their dog, Bounce, witnessed one of the Wright brothers’ early flights in Kitty Hawk. Image credit: U.S. Coast Guard

GE has other connections to the Wright Brothers. Jimmie Beacham, chief engineer at GE Healthcare's Advanced Manufacturing Technology Center comes from a family whose members witnessed the first Wright Flyer flights. Beacham’s great-grandfather William T. Beacham (second from left), grandfather John L. Beacham Sr. (the small boy holding his hand) and their dog, Bounce, witnessed one of the Wright brothers’ early flights in Kitty Hawk. Image credit: U.S. Coast GuardA version of the story originally appeared on the GE Aviation Blog. Sharnoosh Shafie contributed reporting.