Now he is at the forefront of CTE research, and was in 2009 featured in GQ magazine’s “Rock Stars of Science” roll of honour for his research into both Alzheimer’s and CTE. For now, CTE is associated with boxers, football players and battlefield veterans, but Gandy believes other sports will come into question as research progresses.

It will be a long and often heartbreaking road. But in the past year, advances in imaging technology have afforded Professor Gandy the ability to make “during life” diagnoses. That, paired with all that he has already discovered about Alzheimer’s, give him reasons to be optimistic as he continues his research to find answers and interventions for CTE.

GEreports: What can football players, or people playing those kinds of contact sports, do to minimise injuries that lead to CTE?

Professor Sam Gandy: It’s still early days to work out how best to approach it. It’s being approached with smart gadgets, gadgets on the head to measure the torque and forces in various directions, and to follow those people clinically and see how they do, and try to correlate outcomes with these various forces.

Everyone thinks of concussion, loss of consciousness, as the most offensive injury.

That’s not necessarily the case. There are sub-concussive injuries in which the brain is just sort of jostled without loss of consciousness, and those, too, can cause impairment over a long period of time. We see that especially in military populations. They’re often exposed to improvised explosive devices [IEDs], and they’re shaken, but they don’t lose consciousness, but certain people can go on to to get CTE from that.

GEreports: You’ve isolated one gene … obviously there will be others.

Prof. Gandy: Like all of these brain degenerations, I think there’ll be a handful of genes that’ll be important. For Alzheimer’s for example, in a recent study of 75,000 subjects, about two dozen genes seemed to be playing the most important roles.

GEreports: And some of those may crossover with CTE?

Prof. Gandy: I’m sure they will. In fact the one that we’ve studied does crossover.

GEreports: You’ve noted that women can be more susceptible because they generally have longer and less muscular necks. Are there any other physical characteristics that might make you more prone to CTE?

Prof. Gandy: There’s lots of interest in the physiognomy of the skull, the shape of the head, but none of [the research into] that has really been as robust as on neck length and circumference.

GEreports: For people you’ve diagnosed as suffering CTE, what can they do?

Prof. Gandy: We’re trying to apply what we’ve learned from Alzheimer’s disease to CTE because they want to do something now. They can’t all wait for 20 years of research. One thing that helps all of these late-life brain degenerations and protein clumping disorders is physical exercise. That’s been quantified, for Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s; it’s been proven that it will delay onset or if you have the disease it will slow the progression. We haven’t proven it for CTE, but I think there’s a good chance that it will be true for CTE, so I recommend it to people with CTE.

The other is high-dose Vitamin E. It gets tainted with this health-food, squishy-science brush, but in fact two large studies … consistently show that it slowed progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Again, that’s slightly different than CTE, but I think it’s worth a shot. In a two-year study, the folks who were on the high-dose Vitamin E were six months behind the others in progressing. It’s the first evidence that we might have a shot at slowing down these diseases.

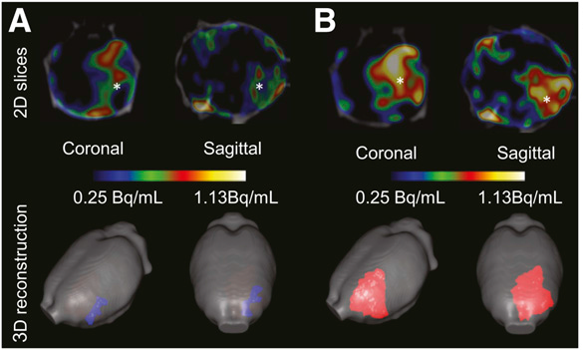

The GE180 detects brain inflammation, a major cause of CTE degeneration.

The GE180 detects brain inflammation, a major cause of CTE degeneration.GEreports: What options do you think you’ll end up recommending? Will there be different ways to play? Different rules?

Prof. Gandy: I hope that eventually we’ll be able to identify both the genetic factors and the physiognomy factors that are playing a role, so that we can at least advise people on what their risk is. I don’t necessarily feel that we have to play a parental role here. But I do think that we’re obliged to do informed consent. If you want to go and accept this risk, at least you should know what it is in a quantified way. Then if you want to take on that risk, that’s your decision.

GEreports: What about skiing, snowboarding, diving?

Prof. Gandy: It will depend at what level of skiing they’re at. Not novice, bunny-slope stuff. But the major, high-velocity skiing with falls, I think are going to be susceptible. Diving? It’s an interesting question. I haven’t seen any case reports, but it may also be true that no one in that world has been sensitive to the possibility and looked for it. Certainly the initial impact with certain types of diving is going to jostle the brain. I think it remains to be evaluated whether that’s going to be a liability or not.

GEreports: Would you let a son or daughter of yours play sports that are at risk for CTE.

Prof. Gandy: I only have dogs, so it doesn’t come up much!

We tried to answer this semi-scientifically a couple of years ago. There were these conferences of experts that were held simultaneously, one on Alzheimer’s disease and one on CTE, because there are lots of people who are interested in both and having cross-fertilisation. So we polled these experts, saying OK you have all the information., have you used genetic testing to predict whether you would let your child play? Long story short: those who had Alzheimer’s in their family would probably do the genetic test, starting with the person with Alzheimer’s. And if they have this [genetic] risk factor, then they would probably test the child to make a decision. Not so much to force the child to go one way or the other, but to have the information, about what sort of level of risk they were putting themselves at.

Because that risk factor is very powerful, it’s not a trivial risk factor. About 15 percent of the population have this risky gene, the one we’ve identified so far. But the NFL is now predicting that 30 percent [of players] will dement. So that’s more than you would attribute to that one gene. So there are other genes, I’m sure, that may also be as important.

GEreports: Are you predicting that we will also see more veterans being diagnosed with CTE?

Prof. Gandy: Yes. CTE, especially manifest as PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. There’s a spectrum there. Not everyone with PTSD has a TBI [traumatic brain injury] or a CTE, but lots of the presentation of CTE is psychiatric. We talk about the cognitive component because of the similarity to Alzheimer’s disease, primarily. But the presentation of CTE is much more commonly psychiatric than cognitive. Depression, violent outbursts … footballers and wrestlers who have killed themselves or killed their families and are then found to have CTE.

GErports: Does it come on many years later?

Prof. Gandy: It definitely does come on many years later. There’s probably the exposure for 10 years, 20 years. Then there’s sort of a latent period where things are quiet for a decade or more. This football player that I was mentioning who was having the memory trouble and came to see us, he’s just turned 70. So his football days were long ago.

GEreports: So that’s why they thought Alzheimer’s…

Prof. Gandy: Exactly. And Alzheimer’s, especially these days—with everyone having some relative or having seen it—it’s what people guess, what they think of first. An interesting tidbit about that story: five of us saw this guy, and we couldn’t agree on what he had. So it was only because we had these scans that we could make the diagnosis. Three of us thought he had Alzheimer’s disease and two of us thought he had CTE. I was actually wrong.

GEreports: So you’re now doing these “during life” scans. Presumably previously these diagnoses were only possible post mortem?

Prof. Gandy: Yes. The first images of tau, of tangles, were just published last year. It’s super new. There are other diseases that were tested first, but the big news now that we’ve just reported is that these tangles of CTE were also visible with this particular ligand, with this chemical. So we also have this test established in this population now.

GEreports: How is the Head Health Challenge going?

Prof. Gandy: Because the disease is so slow ... a one-year study or a five-year study isn’t going to be adequate. We’re not going capture enough of the disease in that short period of time. This isn’t going to be quick or easy. It hasn’t been quick or easy for Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. We’ve learned from Alzheimer’s that we need to get in with these interventions as early as possible. With Alzheimer’s, we don’t know how early that really is. Most people who get Alzheimer’s get it after age 65, do we need to start treating them at 60? 50? 40? 30? When do we start? We don’t really know.

But with these head injuries, we have an idea of the window of time in which they’re going to be exposed, and we could potentially even offer them these medications to take while they’re being exposed to help them mitigate the injury.

Just the whole nature of the beast because you have an exact idea of when the onset is—will hopefully give us a leg up in doing the clinical trials.

GEreports: You’ve been working in Alzheimer’s for quite a long time … the potential to do these “during life” scans is really changing the way you work, isn’t it?

Prof. Gandy: It is, yes. Things that we thought we knew, we find out we didn’t.

GEreport: You threw out a figure that every demented person will cost “someone” one million dollars.

Prof. Gandy: That’s based on Alzheimer’s disease, it may even be more for CTE because the onset is earlier and they tend to be healthy otherwise. Their bodies live on while their brains die. With Alzheimer’s disease, the average duration of life from diagnosis to death is a decade, 10 years. In the US, it’s easy to spend $100,000 a year in a nursing home … just for custodial care, keeping them clean and fed in a nursing home for 10 years.

GEreports: What gives you reasons for optimism in your work?

Prof. Gandy: In the US, there was this extended period of time when the advisors from the NFL, sort of like with smoking and asbestos, were saying, oh no, it’s not the head injury. These people would have gotten dementia anyway. So not only did they stop denying it, they’ve been very pro-active now. And releasing this projection of one-third of their players dementing was not in their best interests.

I knew it was going to be high, but I would have thought maybe one in six, rather than one in three. There are people who think everyone will dement. I think that’s wrong.

Learning more and more about different stages of these brain degenerations. Again, looking at lessons from Alzheimer’s disease with this 75,000-subject study. There are now two dozen genes linked to Alzheimer’s and those can all be evaluated in CTE and potentially be drug targets there, as well. I think it’s turned out to be a major step just to recognise that the disease exists, and to try to have a measured response. You could easily have an hysterical response and I don’t think that’s merited. I don’t think that we need to abolish football at all levels. I would not be thrilled [if I had a son wanting to play]. I don’t know how dictatorial I would be, but I would be very discouraging.

My father’s mother died of Alzheimer’s disease; my wife’s mother has it now, so I see it, all day every day. So it’s made a fairly strong impression on me.

In the past three or four years, there’s been lots of interest from the NFL. I was just approached by the National Hockey League last week, and by the Department of Defense [DOD]. And they have banded together very logically, rather than being silos. Rather than saying, the DOD will take care of the veterans and the NFL will take care of the footballers, there are now review panels, for scientists looking for support for research, on which all of these stakeholders are represented. So that’s very logical and I’m happy to see that there hasn’t been this sort of silo approach.

Being able to make the diagnosis during life, confirm the diagnosis, and begin to think about interventions. Now, since we have a way of measuring whether the drug is doing anything. If you’re stuck with something you can only diagnose post mortem, it’s hard to do clinical trials.