Whenever Dr. Ralf Menkhaus prepares to administer future parents their first fetal ultrasound, he knows the pressure is on: Equal parts thrilled and anxious, expectant parents are desperate to catch a glimpse of their unborn child. Yet, as a fetal medicine specialist, Menkhaus’ top priority is capturing crucial information about the health of the fetus. He’s looking for evidence, for instance, of conditions like spina bifida, a neural tube defect that affects the spinal cord.

Nestled in an emerald valley surrounded by snowcapped Alpine peaks, the village of Zipf, Austria, looks like scenery plucked from a travel brochure. A stroll through the 600-person town reveals such charming sites as a church with an onion-shaped steeple, the Zipfer brewery and plenty of sheep grazing on pristine blades of grass.

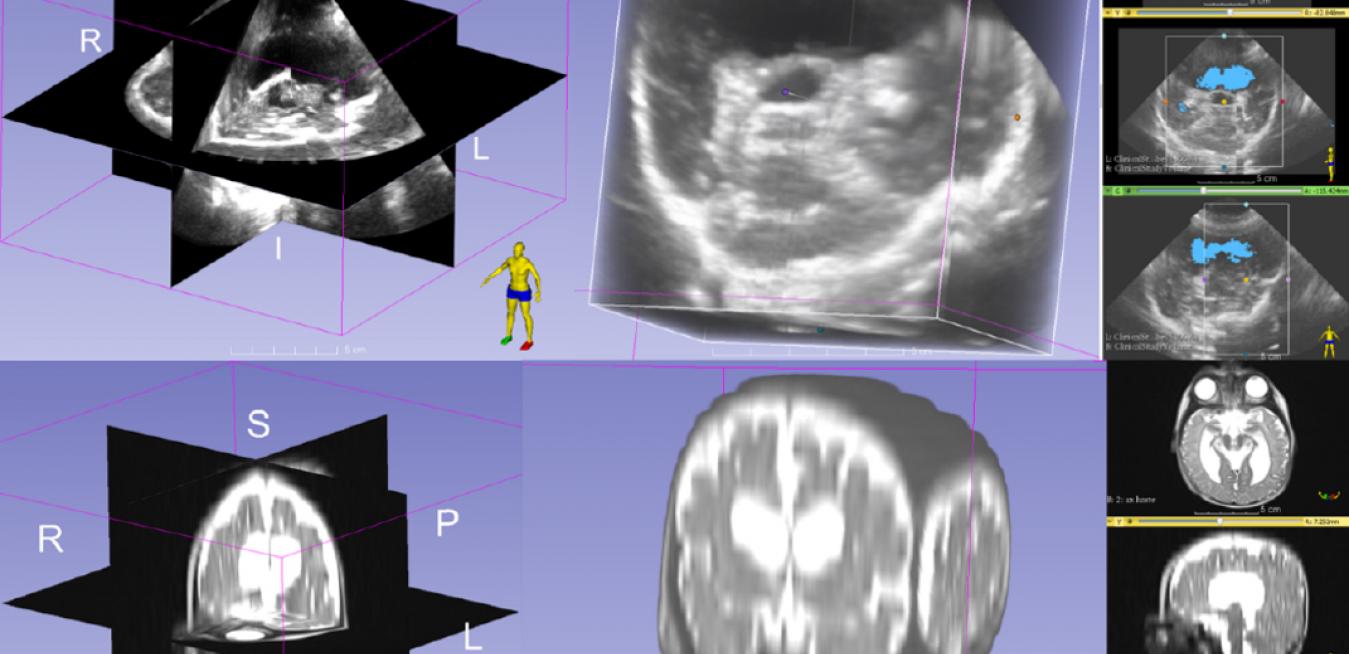

Arzt performs heart surgery on unborn babies, inserting a needle into the mother’s womb and carefully pushing it through a tiny valve in the fetus’ heart that’s just 2 millimeters in diameter, or about as wide as a pinhead. Then he perforates the valve. “If I go 1 or 2 millimeters too far, I tear off the vessel and everything is over,” he says from his office at Kepler University Hospital in Austria, where as head of prenatal care he has overseen more than 140 such procedures.

This year, Rosés got his hands on a new ultrasound system that has changed the way he is able to care for patients like David, who was born with a congenital heart defect.