The Paris Air Show kicked off this weekend with a briefing for journalists — or at least that’s how the jet engine maker CFM International got things going. To CFM, this year’s show is special. Eleven years ago, in 2008, the company announced in a hotel conference room just off the Avenue des Champs-Élysées that it would build a revolutionary new jet engine called the LEAP. Speaking in the same room on Saturday, Gaël Méheust, CFM's president and CEO, told reporters that the jet engine was “delivering on what we promised.”

It started as a lark. GE Aviation’s David Kelly and his colleague Rachel Wagner were working up a bid to supply engines for a fleet of new Boeing Dreamliners three years ago. Since the client, Air New Zealand, had used Rolls-Royce engines for the past 15 years, the whole venture seemed rather quixotic. Success seemed so remote, in fact, that Kelly, GE Aviation’s sales director for Air New Zealand, agreed to jump off the Sky Tower in Auckland if they won the deal.

Drinks in a cozy, elegant cocktail lounge have preceded plenty of marriage proposals. But perhaps only once has such a session led to the creation of the most prolific jet propulsion company in aviation history.

And yet, it happened — in April 1970 at the Ritz-Carlton lounge in Boston, where leaders of France’s government-owned Safran Aircraft Engines (known as Snecma until 2005) came to court GE. Back then, GE was still chiefly building jet engines for the military, and Pratt & Whitney dominated the burgeoning civilian market.

After examining the possibility of ceramics being used in flight in 2001, scientists from the Institute for Defense Analyses starkly concluded, “There may be more pigs flying than ceramics in the future.” It’s easy to see why when you think of a coffee mug: The material is great for handling heat but breaks catastrophically when met with force.

Adventure-seeking bungee jumpers, “Lord of the Rings” fans and hunters of colossal squid have another reason to check out the remote Pacific Island nation of New Zealand: Air New Zealand is expanding its fleet of long-distance jets that can fly nonstop to this faraway wonderland.

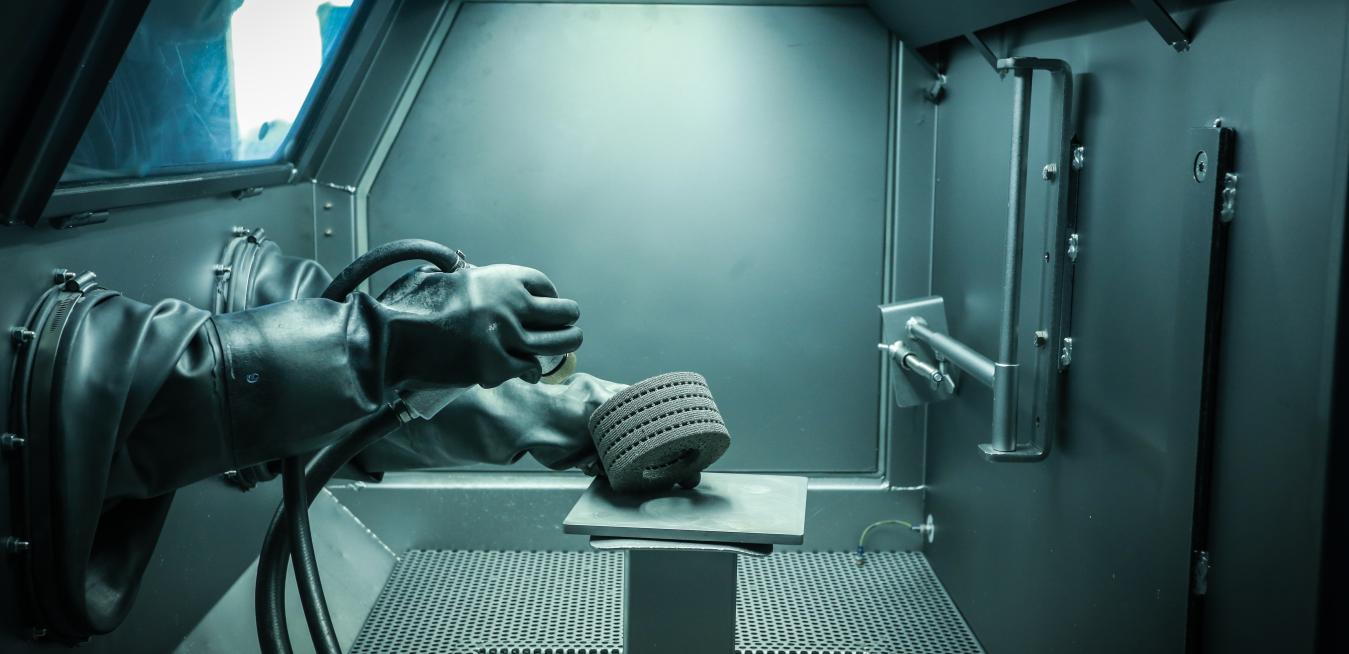

Nestled in the rolling hills of the Po Valley, the small town of Cameri looks like a postcard Italian village, complete with a classic piazza surrounded by traditional-style buildings and a church. It’s a startling contrast, then, that less than a mile from the center of this village sits a major hub of aerospace innovation, anchored by one of largest 3D-printing factories in the world. Operated by Avio Aero, a GE Aviation company, the plant makes the arm-sized blades for the GE9X engine, the world’s largest jet engine.

Qantas Airways made big headlines last year — and generated more than $100 million Australian dollars in free publicity, according to the airline — when it launched the first nonstop flight between Australia and London, a flight path that’s long been called the Kangaroo Route. The flight took off from Perth in Western Australia on March 24, 2018, and landed 17 hours and 20 minutes later at London’s Heathrow Airport.

At the Greene County Career Center in southwestern Ohio’s Xenia Township, 650 high school students spend half their day in the classroom, learning traditional subjects like math, English and social studies. The other half of the day, though, is what gets them most excited.

There are plenty of fast and fancy business jets, but only one that flies the fastest and farthest. This week, the plane maker Bombardier revealed that its Global 7500 luxury aircraft scored a set of records for the longest mission ever flown by a purpose-built business jet and for speed over the longest range (that milestone is still awaiting validation by the National Aeronautic Association).

Until recently, the maintenance department at Emirates, the Dubai-based carrier, was operating by the book. Literally. Ground crews used detailed charts and calendar-based schedules to estimate when the engines powering its massive fleet of Boeing 777 jets needed service.

Airline managers scheduled maintenance every 400 to 600 flight hours — even if nothing was wrong — to perform routine preventative work on their GE90-115B engines, incidentally the most powerful jet engines in the world.