It may have been drizzly in Everett, Washington, but the rain could not ruin the parade at Paine Field, an airport 20 miles north of Seattle. On Saturday afternoon, just as the sun peeked through the mist, a Boeing 777X took to the skies from Runway 16R-34L on its maiden flight. The twin-engine wide-body passenger jet spent nearly four hours airborne before returning to the airport, where it made a smooth landing.

Stefka Petkova enjoys building things. It’s a passion she’s had since she was a small child when her dad, an electrician who liked to work on cars, kept the door to his workshop open. “I was exposed to that as a very young child and just got a lot of encouragement,” says Petkova, who she spent many afternoons watching him weld and wire automobiles.

When Ted Ingling was growing up in a small town in Michigan, he wanted to be a car mechanic. But the plan didn’t work out, and the world might be a better place for it.

The GE9X engine, the largest and most powerful commercial jet engine ever built, is a step closer to full liftoff. GE Aviation recently delivered the first four fully compliant GE9X engines to Boeing’s wide-body plant in Everett, Washington. A pair will take the aircraft maker’s new wide-body passenger jet, the Boeing 777X, to the sky for the first time.

It’s too early to say what the next generation of U.S. Army attack and reconnaissance helicopters will look like. But they’ll be powered by GE engines.

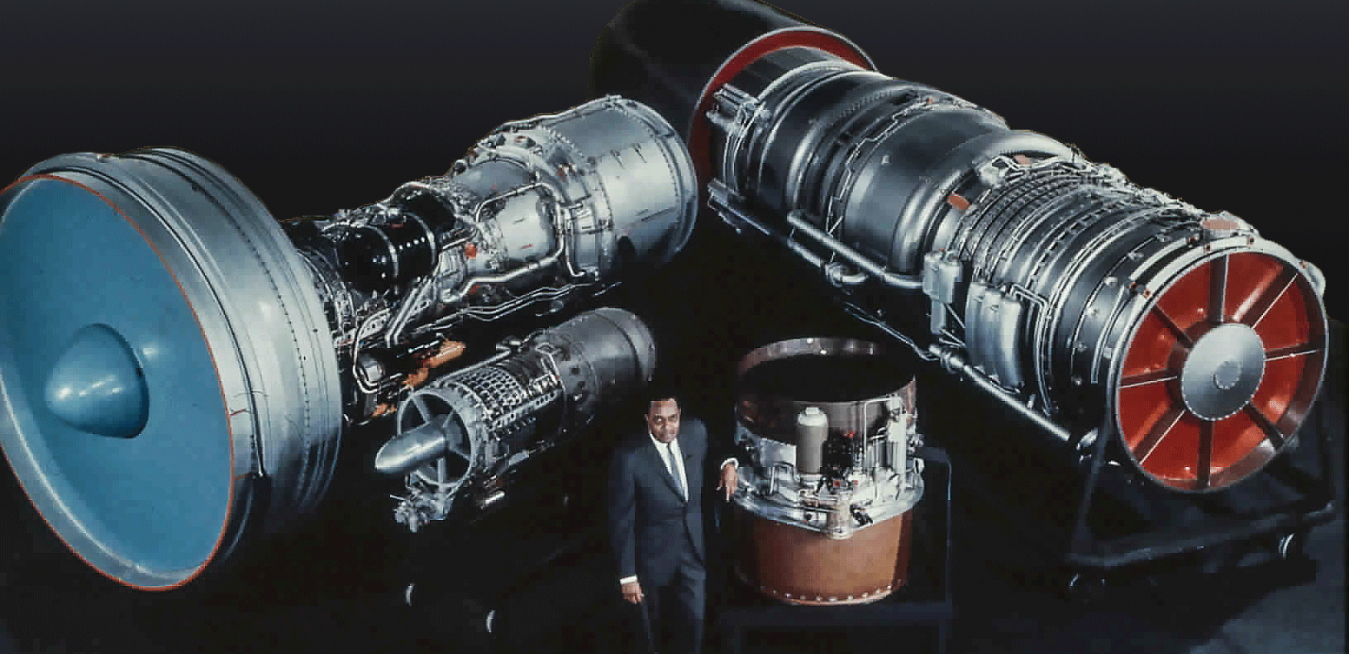

First-time visitors arriving for a meeting at GE Aviation’s headquarters should give themselves a few extra minutes: Located in the Cincinnati suburb of Evendale, Ohio, the plant is huge, security is tight — and there are distractions everywhere. Perhaps the largest, a massive jet engine stretching some 27 feet long, collects dust along a wall inside Building 700. Too big to fit in the company’s museum, which is also located on the Evendale campus, the lone surviving GE4 turbojet is a stunning relic from an era when everything in commercial aviation seemed possible.

Long before AirAsia made a record-breaking $23.1 billion purchase of engines and services from CFM International, the owners of the once-struggling airline had big plans to develop a low-cost carrier.

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, not many GE Aviation engineers could walk as tall as John Blanton Sr. Then one of the company’s few high-ranking African Americans, he was known for doing things deemed impossible at the time. Such as charting a futuristic engine for the U.S. Air Force that could push a fighter jet to travel at Mach 3.5, equivalent to roughly 2,600 miles per hour — enough speed to get from New York City to Los Angeles in just over an hour. Or prototyping an engine that could enable planes to take off and land vertically.