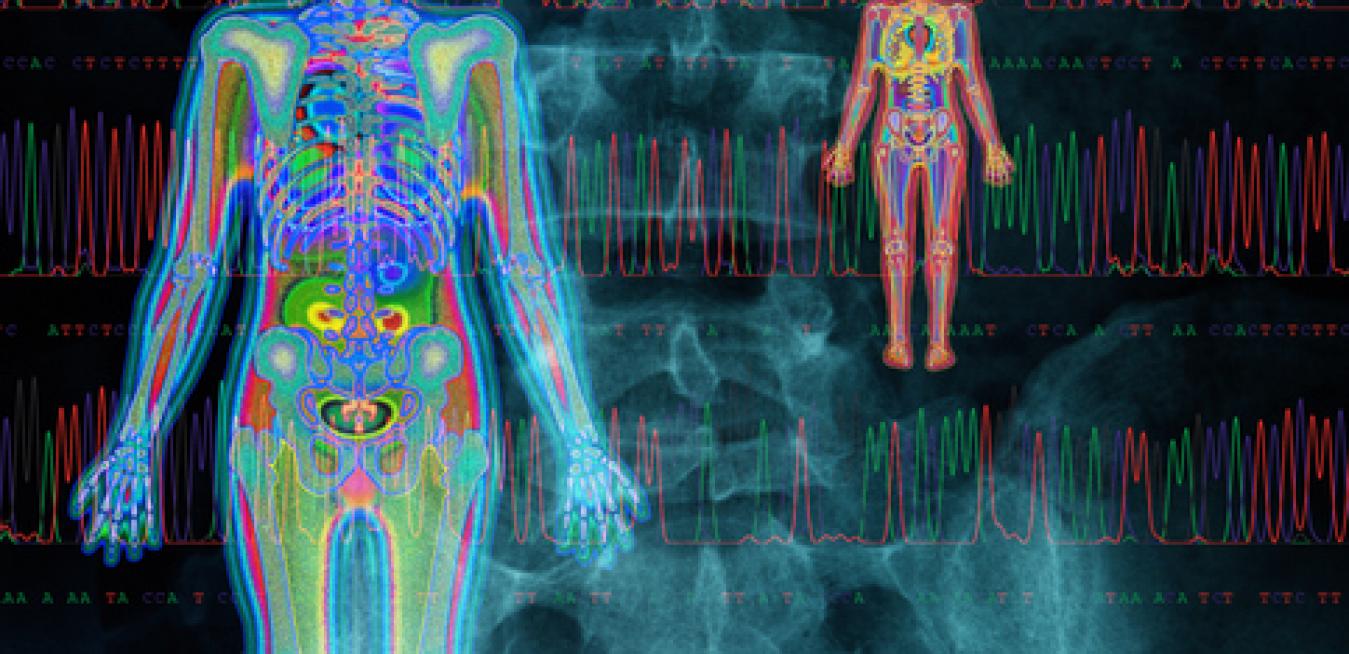

Last year, GE Healthcare and Roche announced that they would collaborate to create clinical decision support solutions on shared digital platforms for so-called “precision health” in oncology and critical care, to be powered by data and smart algorithms.

American nurse Marie Elizabeth Bell recently spent nine months in Papua New Guinea, where she worked at the Kunai Health Centre in the southwestern Pacific country’s remote Gulf Province. One patient left a particular impression on her: a woman named Yaniamo, who had experienced nine pregnancies — twice with twins — but had only six living children. Yaniamo was pregnant again, and when her water broke unexpectedly, she began to fear complications. She needed care from Bell’s clinic — a two-day walk from Yaniamo’s home. So she walked.

Australia’s nearest neighbour Papua New Guinea spreads approximately 462,840 sq km (178-thousand sq miles) and is one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world with more than 800 languages spoken among more than 8 million inhabitants.

Both Ana Paula and Alvaro, who live in São Paulo, Brazil, are legally blind. Their son, Davi Lucas, was strong and healthy, but there was no way their eyes could see the first grainy glimpses of their baby on the ultrasound monitor.

Northern lights and elk steak dinners aside, living in northern Finland is not for the faint of heart. As the region is bisected by the Arctic Circle, local thermometers frequently dip below zero — Fahrenheit, that is — during the winter months, when night reigns in the far north and daylight lasts no more than a few hours a day farther south. The place can also be quite solitary.

General anesthesia, basically a reversible, medically induced coma, is one of the marvels of modern medicine. Carefully calibrated drugs, ventilators and other technology keep patients breathing and comfortable during their most vulnerable moments — and gratefully unable to recall what transpired on the surgical table. From their perspective, it’s simple: Breathe in, breathe out, wake up in a recovery bed. But for the healthcare providers, it’s a delicate art as well as a science.

First impressions can be misleading. In 1895, when Wilhelm Roentgen trained his cathode ray at his wife’s hand and took what may have been the world’s first human X-ray, she cried out, “I have seen my death!” — or so the story goes.

The unit was a goner, but there was no screaming or hand-wringing, and no money was lost. That’s because the entire scene played out inside virtual-reality goggles.