It can be a pain. “Every time I reach for a new slide, I have to take my eyes off the lens and check the forms for that case,” says Ian Cree, professor of pathology at Warwick Medical School in Coventry, UK. “You can get a sore neck from hours at the microscope.”

Mark Frontera’s cellphone wouldn’t stop ringing. It was Thursday afternoon, Oct. 11, 2012, and the engineer was in a meeting with a manager. Whoever it was on the other end could wait, so he sent the caller to voicemail.

A moment passed, and again it rang. He looked at the caller ID. It was Tara, his wife. He excused himself and answered. He could hear the panic as her voice trembled in hysterics.

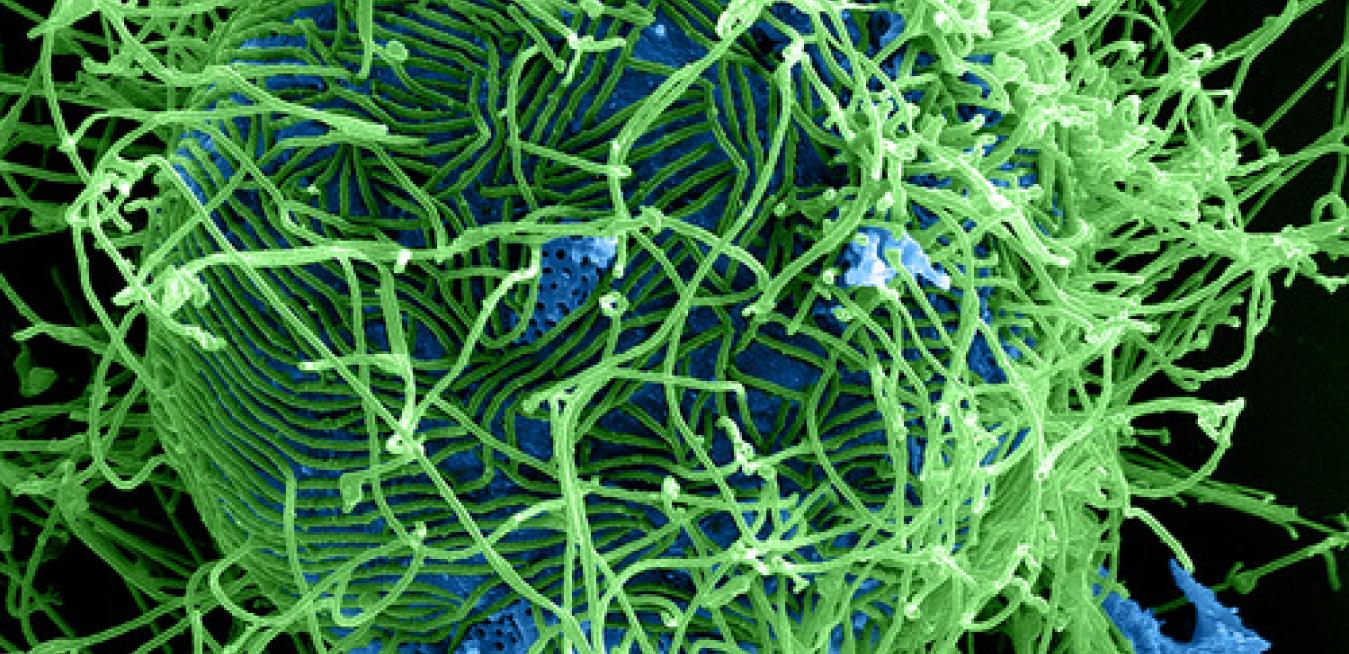

Treating an infectious disease like the Ebola virus is fraught with dangers for both victims and their caretakers. Ebola’s fatality rate can reach 70 percent and an errant drop of blood, vomit or other bodily fluid can turn a nurse or a doctor into a patient.

That’s why engineers and technologists started looking for ways that would allow hospital staff to limit their exposure to the virus when treating the sick.

In 1965, French radiologist Charles Gros built the first X-ray machine dedicated to screening breasts and effectively launched mammography as a viable breast cancer test. The machine, which was built by Thomson CGR, used a special X-ray tube developed by his colleague Emile Gabbay. It was made from molybdenum and emitted low-energy radiation that produced uniform images and contrast that allowed doctors to see breast tissue in greater detail.