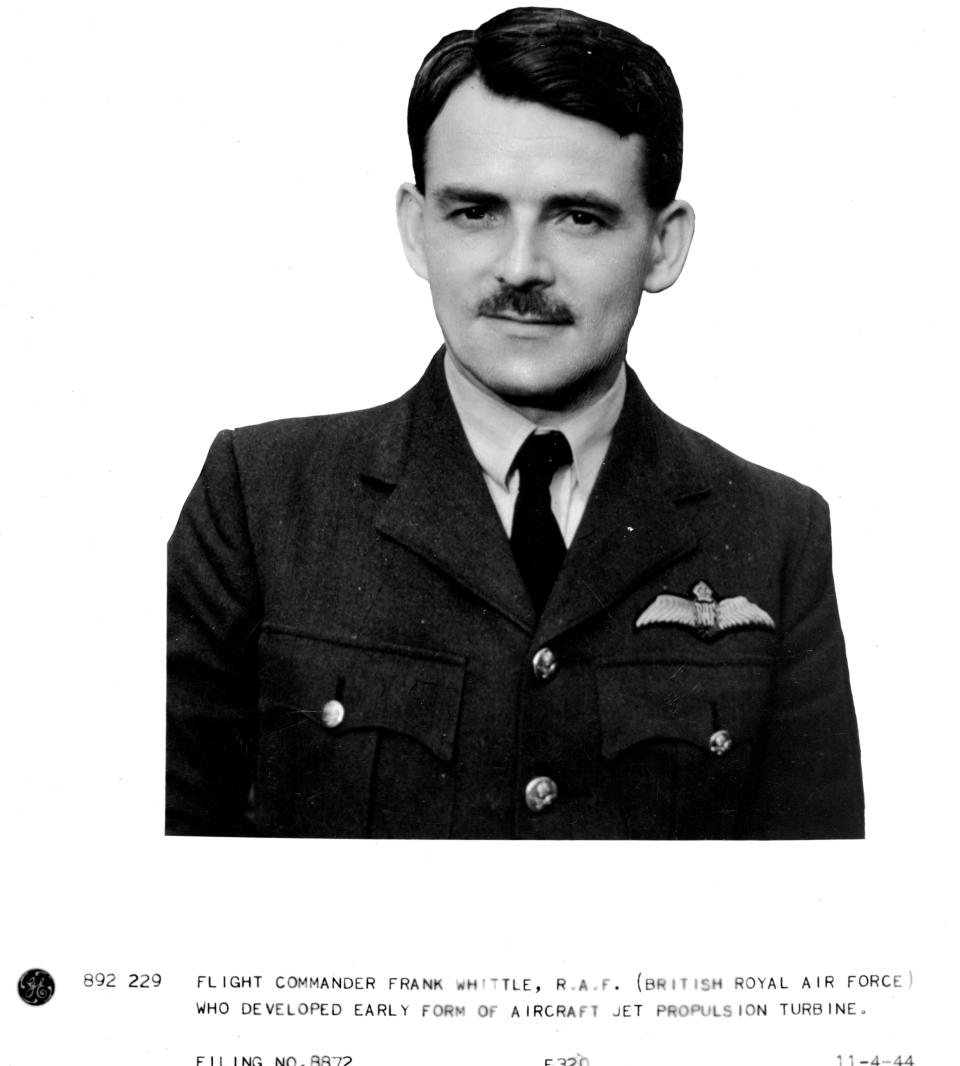

When Frank Whittle’s seaplane landed at LaGuardia’s Marine Air Terminal in New York City in June 1942, the pioneering jet engine designer found himself in a country that prided itself on its technological prowess. And yet, with World War II in full swing, the American jet engines were embarrassingly far behind the British, who themselves had fallen behind their German foes.

Reykjavik in January isn’t the cheeriest place. Darkness reigns for most of the day — the sun rises at 11 in the morning and sets just five hours later. The temperature hovers around freezing, and rain is frequently in the forecast. Earlier this year, 200-some souls waited at Reykjavik’s Keflavik airport to swap the dank twilight for California sunshine. But the plane that had been scheduled for their flight was out of service, and officials were weighing their options.

GE and its partners have received more than $31 billion in new business at the show, which opened Monday. The bulk of those orders are for a new family of LEAP jet engines with 3D-printed fuel nozzles. The LEAP engine was developed by CFM International, a 50-50 joint venture between GE and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines.

Joseph Sorota, likely the last member of the World War II-era top-secret team that designed the first U.S. jet engine, died Saturday at his home in Singer Island, Florida. He was 96.

CFM entered the show with orders and commitments for more than 10,800 next-generation LEAP jet engines, valued at $151 billion (U.S. list price), and the company won deals for at least 393 more. The company sold 565 engines valued at $8.2 billion. The tally includes its CFM56 engines and also business from undisclosed customers.