It’s not an easy time for the global workforce. Companies are contending with an unsettled macroeconomic environment defined by high interest rates, persistent inflation, and stubbornly low consumer confidence. The sheer speed of AI technological evolution is disconcerting for employees.

The GE Aerospace Blog recently sat down with Hannah Gray, who this year was a finalist in the British Ex-Forces in Business Awards for her work as an advocate for veterans transitioning into commercial careers. She leads GE Aerospace’s Military Officer Leadership Program for the U.K. and is also a regular speaker at Officers Association and Forces Employment Charity employment summits, specifically supporting female veterans and those interested in commercial careers.

“Nick Perugini always stood out, starting from the first time I met him,” says David Burns, chief information officer for GE and GE Aerospace. “He had a passion for making connections and this innate ability to build rapport and trust with everyone around him. It’s part of what made him such a great leader.”

Although he hesitated to admit it, Kyle Varble was confused. Fresh out of college, he was working in procurement at a manufacturing company, where every day brought some new bit of unfamiliar jargon. One day a supplier told him that the parts Kyle needed wouldn’t arrive for two weeks, because they had to sit on the CMM machine. His mind raced. What does a CMM machine do, and why does it take that long? What does “CMM” even stand for?

Like most leaders in GE’s Pride Alliance, Liam Richards didn’t show up to work with a burning passion for social justice. His passion was for flight, which as a youth in England he pursued via a private pilot’s license and a degree in aerospace engineering. In 2012, Richards signed up for a local blood drive, where he was first obliged to check “homosexual” on a screening form and then was promptly barred from participation. “This was one of the first real times I came across discrimination,” says Richards, who’d grown up in London and been openly gay since he was 16.

At five foot ten and 145 pounds, Alex Gold knows he’s built for speed and distance. “When I tried out for my high school track team, I ran a mile in 5:38, which is really exciting for a freshman,” says the 28-year-old GE Aerospace engineer. “But I really had no idea what I was doing.” It was only when he started training with older mentors on his team that running exerted its deeper pull. “Right away, I could see that it was the one sport where when I put in the work it showed up in results,” says Gold.

When she was a little girl, every Friday for six years of her childhood in Columbus, Ohio, Devon Shepherd’s family would get in their minivan and drive to the airport to watch planes take off and land. Shepherd marveled at how amazing they were. What makes them fly? she often wondered.

About five years ago, Alex DaRosa was watching a colleague deliver a presentation to the Pilot Advocacy Group at GE Aerospace when he had one of those life-altering “aha” moments. The speaker was Walt Moeller, who works in flight operations, writing engine manuals for pilots. But for many years, Moeller’s main job was flying commercial passenger jets. “He basically came in and talked about his time being a captain for Comair and how that was his favorite job of his entire life,” DaRosa recalls.

Loren Finnerty manages more than 300 shop floor workers and engineers at GE Aerospace’s giant Asheville plant in North Carolina, where thousands of advanced composite components are produced every year for GE jet engines, such as the GE9X, as well as the

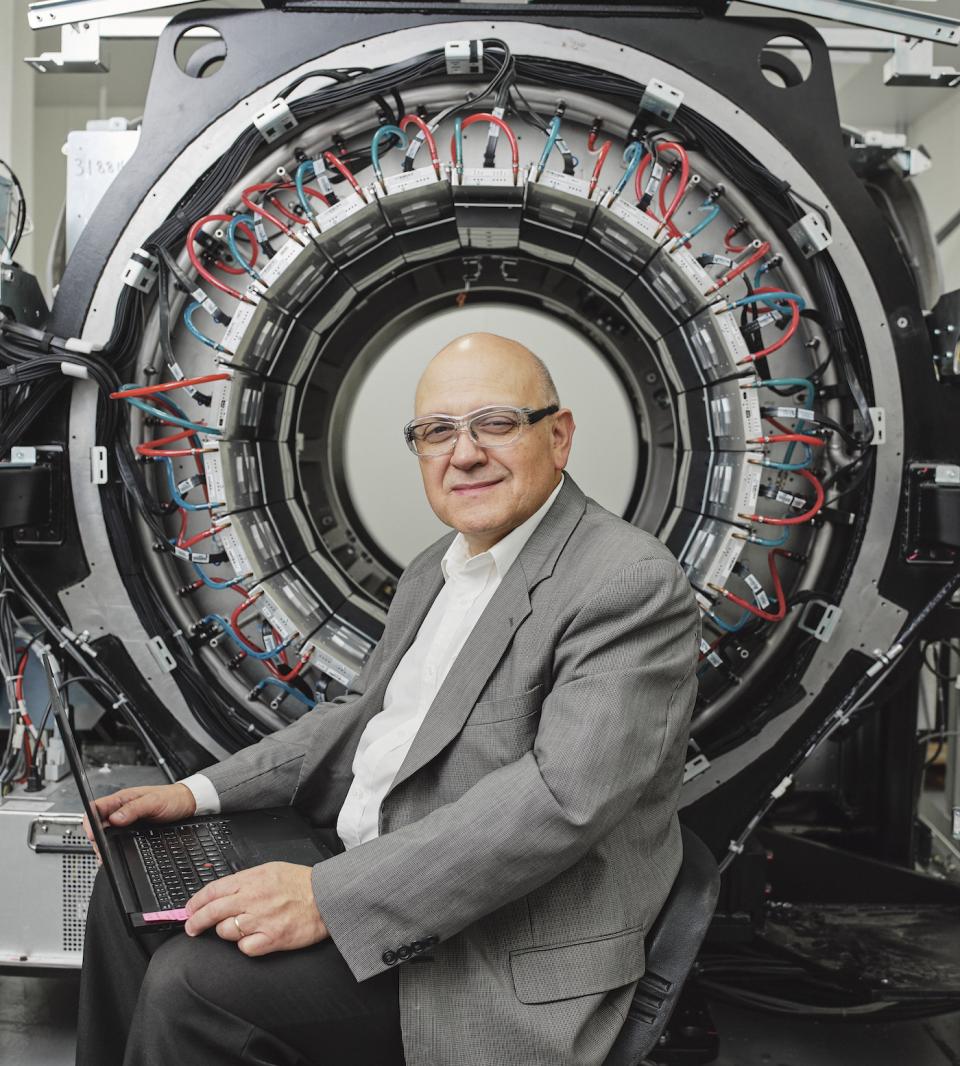

In western Colombia — surrounded by towering mountains, an active volcano, and lush green coffee plants — lies the picturesque city of Manizales. In addition to being the heart of Colombian coffee production, the small community is also the hometown of Jorge Uribe and his father, mother, brother, and two sisters.