The history of GE and modern aviation are closely linked. Few symbols embody the connection more than the original GE flying testbed, a 49-year-old Boeing 747-100 that served as an airborne lab for engineers testing generations of new jet engines. The plane, the last operating model of the first variant of the iconic 747 jet, made its final flight earlier this month.

Reykjavik in January isn’t the cheeriest place. Darkness reigns for most of the day — the sun rises at 11 in the morning and sets just five hours later. The temperature hovers around freezing, and rain is frequently in the forecast. Earlier this year, 200-some souls waited at Reykjavik’s Keflavik airport to swap the dank twilight for California sunshine. But the plane that had been scheduled for their flight was out of service, and officials were weighing their options.

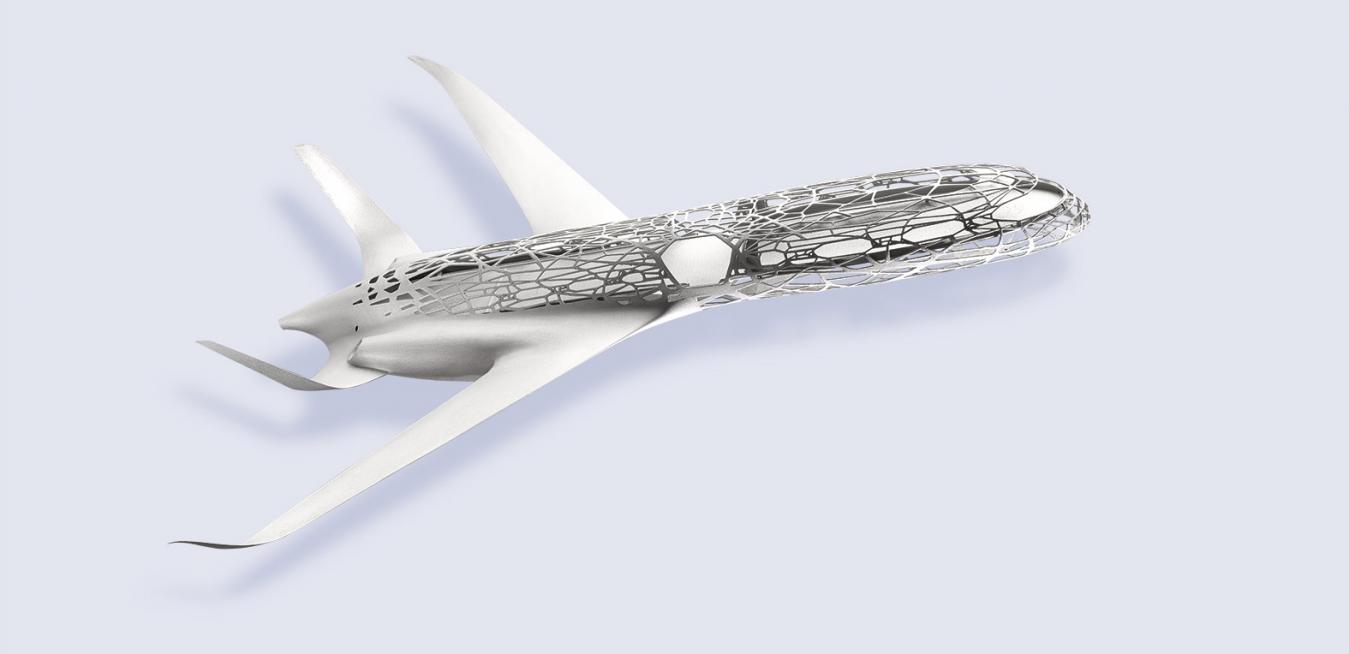

It’s A Bird. It’s A Plane. It’s A Supermaterial!

It’s been a week splashed with sunshine at the Farnborough International Airshow — an unusual sight for England in July — but GE Aviation still made it rain. The GE unit that makes aircraft engines, plane components, avionics and other aerospace technology said it and its partner, CFM International, have won orders valued at more than $22 billion at list price.

But to do that, Allegheny needed wings. It bought regional carriers like Indiana’s Lake Central airlines and New York’s Mohawk Airlines to provide coverage east of the Mississippi River and in parts of Canada. But it still wasn’t enough. The problem: Planes are expensive and Allegheny couldn’t afford to buy the new aircraft it needed.

GE and its partners have received more than $31 billion in new business at the show, which opened Monday. The bulk of those orders are for a new family of LEAP jet engines with 3D-printed fuel nozzles. The LEAP engine was developed by CFM International, a 50-50 joint venture between GE and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines.