Nicole Cripps had just printed the very first design on her school’s brand-new polymer 3D printer when she found herself in a pickle. Her model of a small cube refused to budge from the machine’s base plate. “I thought, ‘Whoops! I’ve broken it first go,’” remembers Cripps, a librarian and STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) teacher at St. Joseph’s Catholic Primary School Riverwood in New South Wales, Australia, which received the printer from the GE Additive Education Program (AEP) in 2018.

Cripps quickly emailed her AEP support team at Polar3D to discover that, much to her relief, she had not destroyed the printer, and could bend the base plate to cleanly disengage her model. “Whilst I’m sure they had a laugh, they were very supportive,” she says.

Anecdotes like these are precisely the stories that AEP’s creators love to hear. They get at the heart of how this program has engaged over 1 million students within three years: building a supportive community of 3D-printing learners to prepare the next generation for the digital age.

In 2017, GE Additive — a GE unit that makes industrial 3D printers for metals, sells materials for printing and offers consultancy services — launched the five-year AEP program to draw more kids into STEM education and show them the potential of learning 3D printing.

Above: Students at Deerwood Elementary school test their 3D-printed mazes. Top image: Students submitted snowflake patterns in a recent contest by the GE Additive Education Program. Image credits: GE Additive.

Among other educational initiatives, the program delivers polymer 3D printers to primary and secondary schools around the world. GE Additive recruited Polar3D — a Cincinnati-based company that provides an online platform for 3D printing in education known as the Polar Cloud — to design the educational program and help GE Additive oversee the AEP.

Schools caught on to the idea fast. In just three years, roughly 1.3 million students from over 2,000 schools in 36 countries have participated in the program. That includes 800,000 kids from nearly 1,000 primary and secondary schools accepted into AEP this year.

But a community like this, one dedicated to transforming how kids learn on a global scale, can only flourish with teachers like Cripps leading the charge. Worryingly, in its first year, AEP coordinators noticed from Polar Cloud data that roughly one-third of participating teachers were letting their 3D printers sit idle.

Part of the problem was that most had no idea how to use the machines. Only 30% of schools had ever owned 3D printers before joining the program, and less than 5% incorporated 3D printing into their STEM curriculum. Problems had the potential to multiply, given that transforming a design into a model historically involved many steps — each subject to potential missteps — such as downloading designs to the schools’ operating systems, and then using thumb drives to run the print job itself. “This all changed with the Polar Cloud platform,” says Greg LaLonde, CEO of Polar3D. “Think early stock exchange days compared to the high-frequency trading of today.”

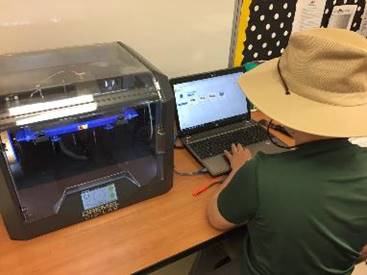

A student at Three Rivers Elementary school uploads an object to the 3D printer. Image credit: GE Additive.

Since 2016, Polar3D has been developing its Polar Cloud platform. Now, schools can teach the entire program from the platform, accessible from any device with a browser. 3D printing is as straightforward as logging into the Polar Cloud, selecting a design and sending it to print.

Like many of the teachers involved in AEP, Cripps was new to the technology. So, she delved into AEP’s required training program, a series of documents and webinars, to bone up on CAD (computer-aided design) software like Tinkercad, Fusion 360 and Makers Empire 3D. “My learning curve has been steep!” she says. “I used Makers Empire with the students myself last year, and we helped each other learn new tips and tricks.”

In the meantime, the team at Polar3D monitors the progress of Cripps and her fellow participants with a reporting tool that alerts them when machine usage begins to flag. “We can reach out to those teachers to see why they are not engaged and provide support,” says Dean Morris, who as the community manager at Polar3D helps oversee the program. “Far, far more often than not, once the teachers embrace it, the program falls into the place. The students pop in to class and watch their designs appear. It’s a powerful experience.”

This kind of expert assistance might give teachers a gentle push into 3D printing. But it’s also their peers who keep them coming back to learn more. Early on, Cripps connected via the Polar Cloud platform to another local teacher participant, who has since become her sounding board for new ideas and challenges. In addition, she recently purchased earring hooks to teach 3D-printed jewelry based on a tip she got from another teacher.

To keep those conversations flowing, Polar3D has set up discussion groups on its platform and encourages teachers to visit social media outlets, such as the AEP Facebook page.

The GE Additive Education Program’s (AEP) will grant polymer 3D-printing packages to 982 primary and secondary schools and reach 793,000 primary and secondary school students in 23 countries. Since its foundation in 2017, over 1,296,000 students and 2,000 schools in 36 countries have benefitted from the AEP. Image credit: GE Additive.

Like their teachers, students thrive from connecting and collaborating with fellow makers on the Polar Cloud platform. Kids can share their designs on the platform, where others can comment, make adaptations, or print their own. “What’s cool is that 3D printing isn’t just for engineers, but artistic, creative types too,” says Mark Meyer, an engineer at GE Additive who helps run AEP in addition to his day job.

And Polar Cloud design competitions add an extra layer of excitement. Last December, AEP challenged its students to submit snowflake designs using specific kind of modeling software; the winners selected by a panelist of experts came from Belgium, Pakistan and the United States. “Years down the road, we will ask ourselves why we didn’t begin networking and collaborating with the community outside our classroom sooner,” says Morris.

This year AEP students will be turning their attention to the world of commerce with a brand-new online store selling student’s original designs. Visitors can also use it to search for nearby schools, visiting their homepage to buy printed designs or donate to the school. Like a bake sale, all proceeds from sales go directly to participating schools, who can use the funds at their discretion. One school in Nova Scotia, Canada, raised $600 for a nearby children’s hospital. “Students’ appetite to showcase their work is insatiable,” says LaLonde. “And the school store is an opportunity to develop and reward student entrepreneurship.”

Students gain invaluable life skills along the way. Last year, Cripps’ 11-year-old student Taylor made an iPhone case that “looked fantastic but did not fit my phone.” After analyzing her work, Taylor realized that she had missed certain measurements crucial to 3D design. “I must have missed looking on the underside of my phone case, as my design stuck through the back where the phone sits,” Taylor concluded. “Next time, I will look from every direction.” With that kind of persistence and self-reflection, she’s bound to get things right.

This article was originally published on GE Reports.