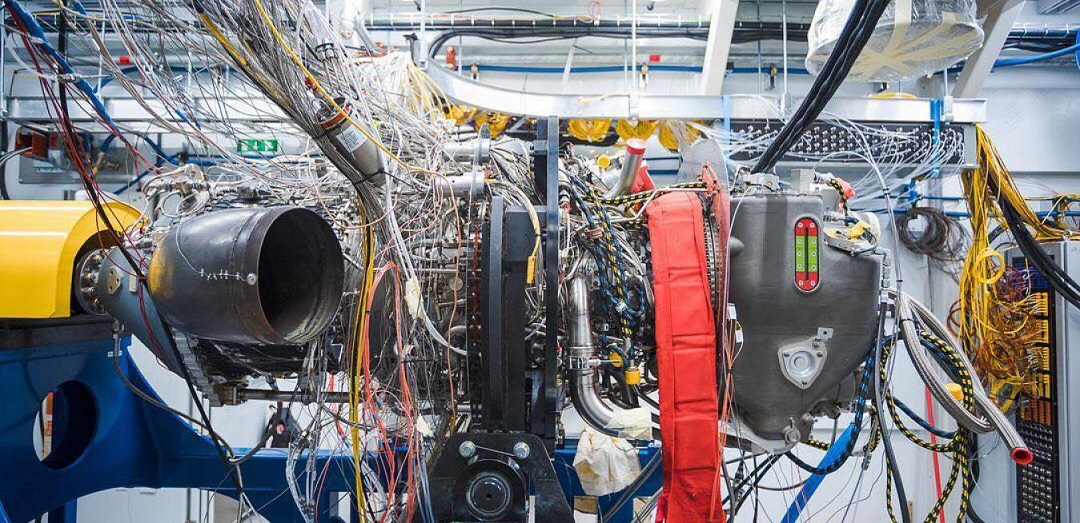

When you first see it, GE Aviation’s new 3D printed Catalyst turboprop engine looks a little like a piece of captured alien technology. Strapped to a metal bed inside a concrete hangar on the outskirts of Prague, the gray metal machine bristles with some 500 silver cables connected to external and internal sensors. The probes collect information about vital factors like vibration, torque and thrust and send it to a team of engineers working in a nearby windowless room. Some of them are watching the test on TV screens while others, huddled like sound engineers at a large mixing board, push and sometimes torture the engine by striking computer keys and flipping switches protruding from banks of equipment. “There’s not another engine like it in the world,” says GE Aviation test engineer Stephen Erickson.

Erickson is right. Besides being the first new turboprop designed from scratch in more than 30 years, the Catalyst is the first engine destined for mass production with large sections 3D-printed from metal. GE engineers used the technology, also known as additive manufacturing, to distill into just 12 printed parts what typically would amount to 800 components if they were made by conventional methods. The approach enabled them to reduce the engine’s weight by 5 percent and improve specific fuel consumption by 1 percent. The technique also allowed the team hasten its development “from a dream to a reality in just two years,” Gordie Follin, the executive manager of the Catalyst program, told GE Reports. The normal cycle to get to a running engine is usually twice as long, and it can take up to 10 years to develop. “With additive manufacturing, we’re disrupting the whole production cycle,” he says.

Learn more about additive manufacturing machine solutions.

Follin was on hand mid-March in Washington, D.C., when Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine gave GE Aviation a Laureate Award in the Business Aviation category for its work on the 3D printed Catalyst parts. “GE Aviation and this year’s winners exemplify the spirit and innovations that are transforming our industry to meet the challenges of tomorrow,” said Joe Anselmo, editorial director of the Aviation Week Network.

But the Catalyst’s innovations don’t stop with 3D printing. The engine also sports technology called full authority digital engine and propeller control, or FADEPC, which is common in jets but has never been used in commercial turboprop planes. Essentially the engine’s digital brain, the technology will allow pilots to control a plane with just a single lever, instead of three. FADEPC will make flying turboprop planes so easy “my mom could do it,” according to GE’s Simone Castellani, an Italian aerospace engineer and aviator helping develop the technology. “Everything is done automatically. In a way, it is just like flying a scooter.”

The first plane powered by the Catalyst including 3D printed parts will be Textron Aviation’s new luxury business aircraft, the Cessna Denali.

Top image: The GE Catalyst on a test stand in Prague. Image credit: Chris New for GE Reports @seenewphoto.

This article was originally published on GE Reports.